You are here

Maps as evidence of site-specific experiences and their role in just decision-making

Establishing Presence

In the neighbourhood of Chembur, Mumbai, we come across street maps showing us the layout and names of the plots on that lane. It’s a simple locator map; houses are mapped in a straight line (an arrow at the bottom says: you are here), delineated by shape and labelled with names. Both shape and name carry a story — some contextual information — Nancy is always learning more about Mumbai and its socio-economic and cultural history, and fills us in on what these markings indicate.

I had meant to talk to Nancy about maps while we were at the Multispecies Canvas in Mumbai, things she learned while working at Technology For Wildlife Foundation (TfW) and her continuing role in conservation and science communication, but it feels like a wonderful coincidence that we have this conversation by chance, coming across a map in the street on a Sunday morning walk.

Or perhaps it’s a Nancy thing. Maps are kind of central to orienting herself in this world—maps, old and new, are to be studied before going to a new place, walking and cycling routes are to be traced in real-time as a way of personal record-keeping, and the tools and process of map-making is the first and foundational step in any creative or research-oriented work.

As a format, maps help establish location and record all that is deemed significant in conjunction with it. But the process of map-making is not without inherent biases—we are attuned to seeing certain stakeholders and overlooking others. Official maps in their clinical representation and rigid compartmentalisation often omit the felt experience of the site, the multispecies, polyphonic, and plural reality of existence, where many realities are constantly rubbing shoulders and cumulatively creating the experience of presence for one another. Disconnected from this aliveness — the beach frequented by both regular morning walkers and many species of crabs, the flight paths that bats navigate using environmental landmarks as acoustic waypoints, the droning chorus of frogs at dusk as seasonal reassurance —the map as a record runs the risk of reduction to simple lines, a flattening both literally and figuratively.

In Whose Land is it Anyway, the researcher challenges the rigidity of this approach, instead working with the idea of stories and lived experiences as an operational layer to visualise the impact of boundaries on the people and relationships within the Bannerghatta National Park in Karnataka. It borrows from counter-cartography practices, that is, a map that counters existing structures, narratives and power dynamics to offer an alternative, intimate documentation of a place that comes from a long history of coexistence, often inextricably linking land, water, and sky to all other life forms. The resulting map may be considered as community records, part evidence of collective presence and part assertion of relational value, identity, and rights that are often ignored in traditional cartography practices.

Connecting Threads

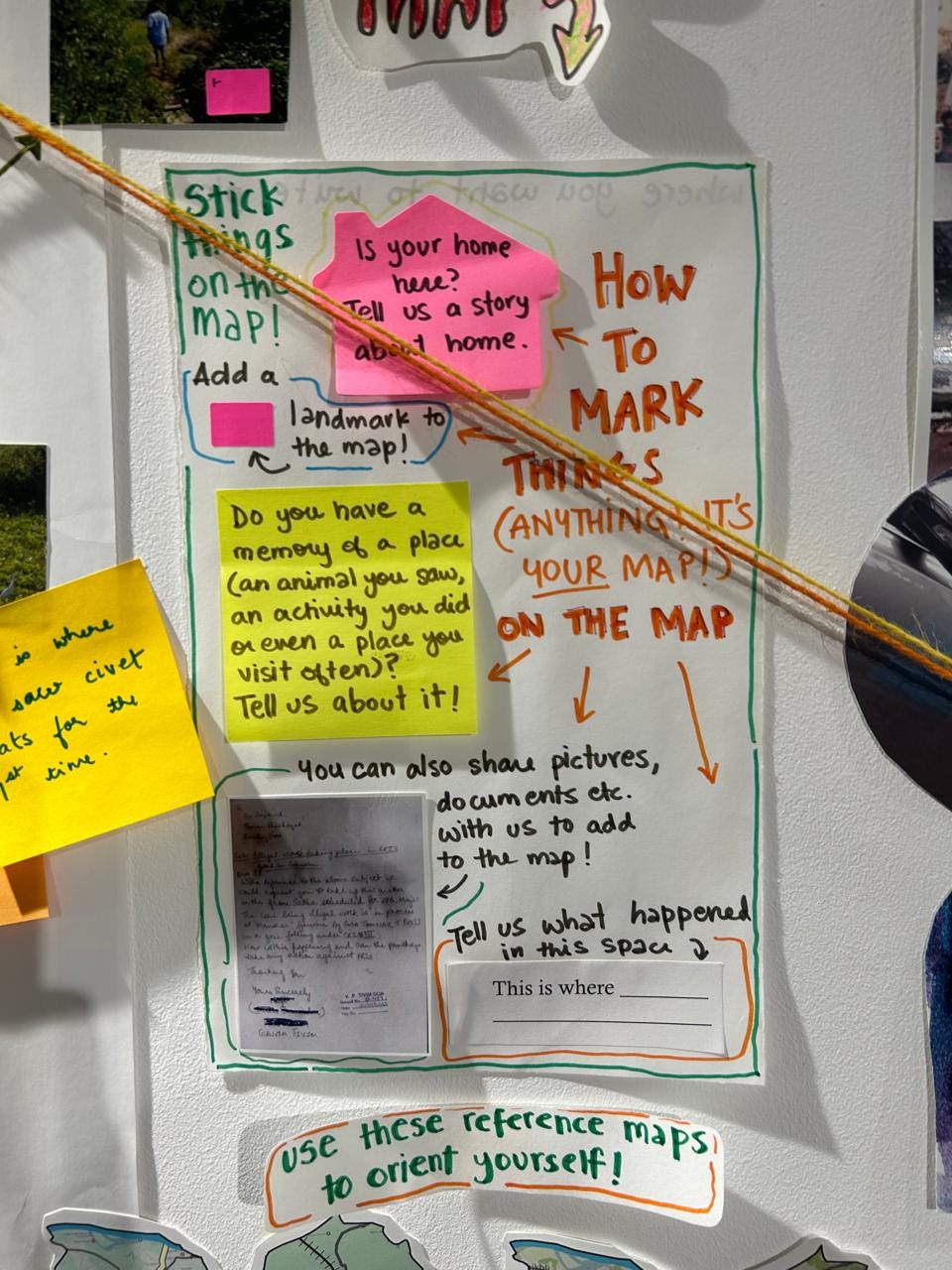

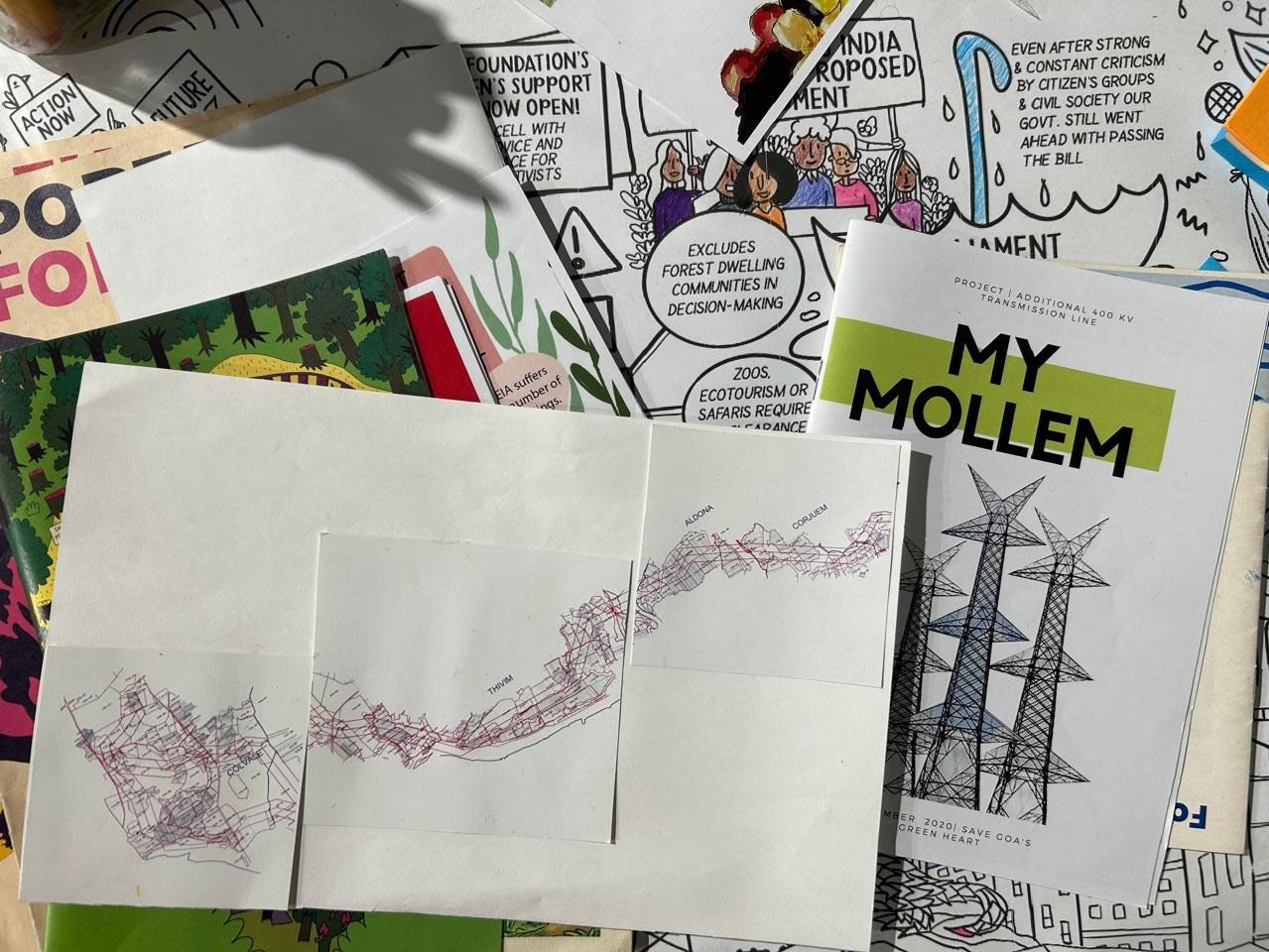

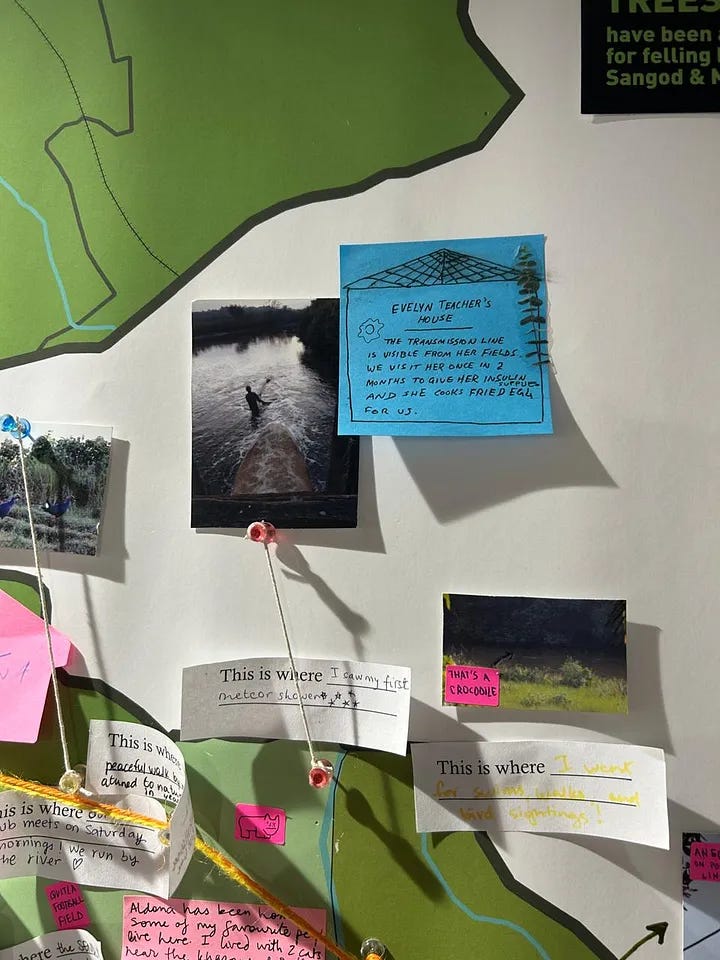

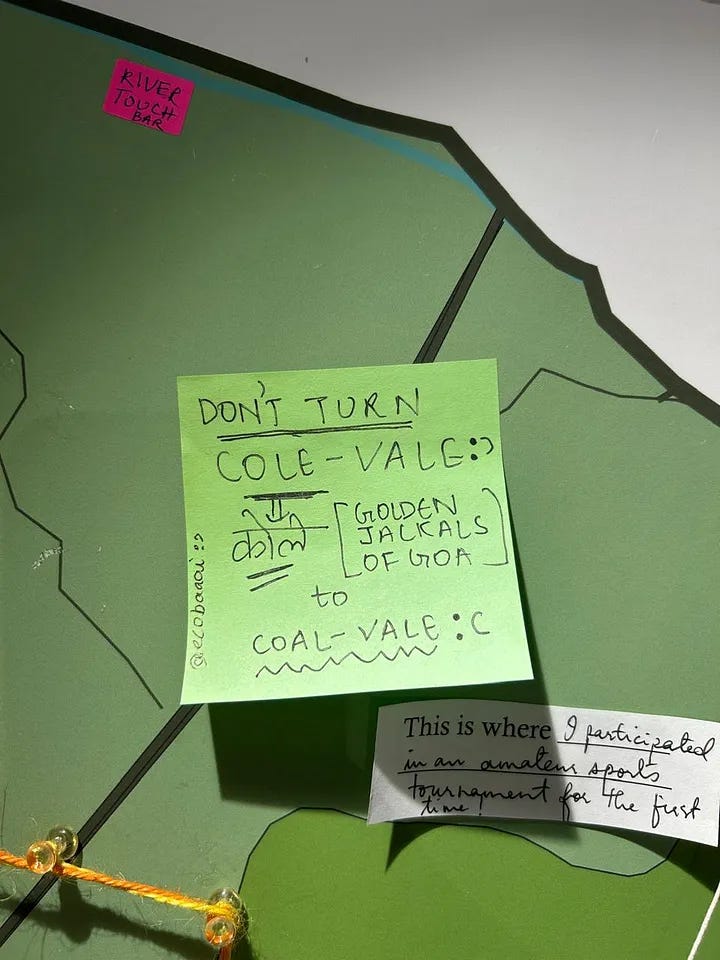

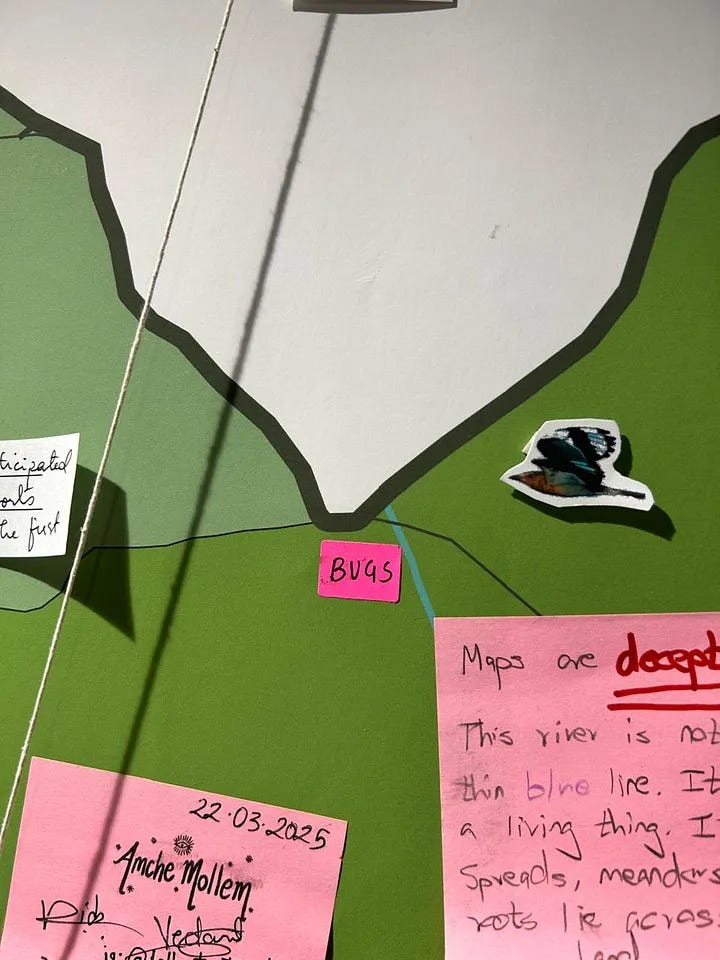

Closer home, at an exhibit at Arthshila in Nachinola, Goa, a counter-mapping exercise has been underway all summer. I reach out to Rhea for a walk-through of the map she led the creation of, on behalf of the Amche Mollem Campaign, for the Kaghazi Pairahan exhibit. The map takes the shape of a wall-sized collage: including photos, notes, anecdotes, memories, local landmarks for reference, and a thread that originates in the forests of Mollem in South Goa and cuts across the state to reach the villages of Aldona, Corjuem, Tivim, and Colvale in North Goa, neighbouring where we are now. The thread follows the route of the proposed Goa Tamnar Transmission line, one of the three infrastructure projects in Goa that citizens and lawyers have been advocating against for the last five years.

The question at the heart of this exercise is: What is the value of this forest that is being hidden from people in an attempt to get these projects passed?

R: We’ve tried to talk a bit about the value of this forest beyond development projects that are coming up. What do we really lose? And a part of that is obviously documenting wildlife and plants inside the forest that would be impacted. But one thing that we really wanted to talk about was people's connection to the forest and how people felt about it.

The map, as it’s coming together, is in stark contrast to the ‘more basic and technical’ maps that are included in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports, an assessment process mandated by law to obtain Environmental Clearance for such projects.

R: The EIAs left out a lot of important species. They were done in very short periods of time, in the lean seasons, like the summer, when you can't see any frogs. I'm not an expert in this space, but I've always really wondered how the court decides that this is acceptable evidence. Someone going to the forest for three days in the summer versus a group of people who live in a place and care about a space, actually documenting it for themselves.

T: Do you know if they also consulted with the forest department and took their views on the kinds of species of plants/animals/biodiversity? Or looked into People’s Biodiversity Registers?

R: I don't know, I can find out. As far as I remember, in the EIA document itself, there was no reference to how they made the list other than that they did these surveys. It just says, we did these biodiversity surveys and here's the species count. I doubt they saw all of the animals that they actually documented. So there would have been some looking at, say, reference lists.

The map in front of us is neither a scientific study nor does it represent a complete picture of the social and environmental impact. What it does, however, is invite people to consider their surroundings, find personal associations with the site, and see how others relate to it as well. It’s a collective activity that reveals the soft power of memory, sentiment, and care — bringing closer and making real the events taking place inside a ‘distant’ forest. The active engagement that counter-mapping requires lays the ground for reflecting on notions of citizenship, resistance, and solidarity, and provides essential support for often drawn-out and exhausting legal battles. Co-creating the artefact is a playful activity and requires some imagination.

R: I was trying to make it as friendly as possible. Despite how haphazard the map looks, people still go, ‘Oh, what if I do the wrong thing?’ I think it's also something we're taught; that maps are technical, and so you have to know how to map, to be able to put something on it.

T: Is this more for the general public, or is there a possibility of such a map making it to the ongoing legal case and being submitted along with that?

R: It would be really nice to be able to do that, but I don't personally know too much about how evidence works or what the feasibility of certain forms of evidence is. What we did earlier was run the whole campaign external to the court case. The case was supported by a lot of research that came out of the campaign, but a lot of it was just part of the campaign. But it was still referred to in the Supreme Court judgment. I think maps are a huge part of a lot of court cases. So for most development projects near or inside a forest, it's very useful to make a map that shows, maybe more technically than this does, that this is a sacred grove or such.

T: But what would more technically mean?

R: So that it looks like something the court wouldn't go, ‘guys, come on…’

T: ‘…this is not arts & crafts!’

R: Yeah, that this is not a craft project! Which, I mean, I would love it, I would be so happy if I were a Judge and someone came to me with this.

T: Are you going to make a digital version of this?

R: Yeah, we want to. How do we digitise this in a way that is obviously appealing to people and is emotional? I feel this is a much more emotional way of showing things. But to also have something that goes along with it, which is less emotional, in a way that a court will look at it and say, okay, no, this is emotion, but it's portrayed in a way that is acceptable — Personally, I would say this should be what's acceptable in court. I think it also ties a lot to what we were talking about in Bhopal about the idea of representation and creation of evidence, and why this is or is not valuable evidence.

Whose story is it?

Where is the story unfolding? How does an event in one place affect something elsewhere? In When The Earth Testifies, the enquiry also leads us to consider the suitability of maps for communicating questions of environmental justice. Whose sentiments are being accounted for in the decision-making process? What indicators should be considered in assessing impact?

It was while working on Issue 3 of the Code Green newsletter that I first came across research from Malaysia, on mapping public social values to inform local flood management plans (see infographic on the mapping process). Usually, such softer, more intangible relationships with the land are often excluded because they are harder to quantify. In the accompanying podcast, Izni Zahidi explains that by engaging with the residents of Kuala Selangor and their familiarity with the area and lived realities as part of the spatial analysis, more effective decision-making and climate action is possible at the local level.

The February issue of Question of Cities reinforces the point that the missing piece is often the community affected by both the impacts of climate change and the resulting policies. It documents case studies in Mumbai and Hyderabad where people are mapping their neighbourhoods for climate vulnerability. The framework they propose for such localised data and assessment is not just to measure damage but to build resilience, and similar to Izni, they hope that it can inform climate governance and policy-making.

R: I like to think about mapping more from the perspective of why am I making this map? Who am I mapping for? Whose land is it?

Maps are basically a spatial representation of knowledge. It's some knowledge about a space, and that knowledge is actually built from experience and the way we experience a space and the best person to talk to about your experience of a space is a person who lives there / who's lived there for a while / who interacts with the space intimately / who has a perception of it built out of this experience.

The idea of building a community map may look like a collage on a wall or a participatory workshop currently, but research for Code Green also bought up the example of the Malaysian state of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo, where community-made maps, made using handheld GPS devices and GIS softwares, were presented as evidence in ongoing litigation for previously undocumented native land rights to be legally recognised and thus protected for generations to come.

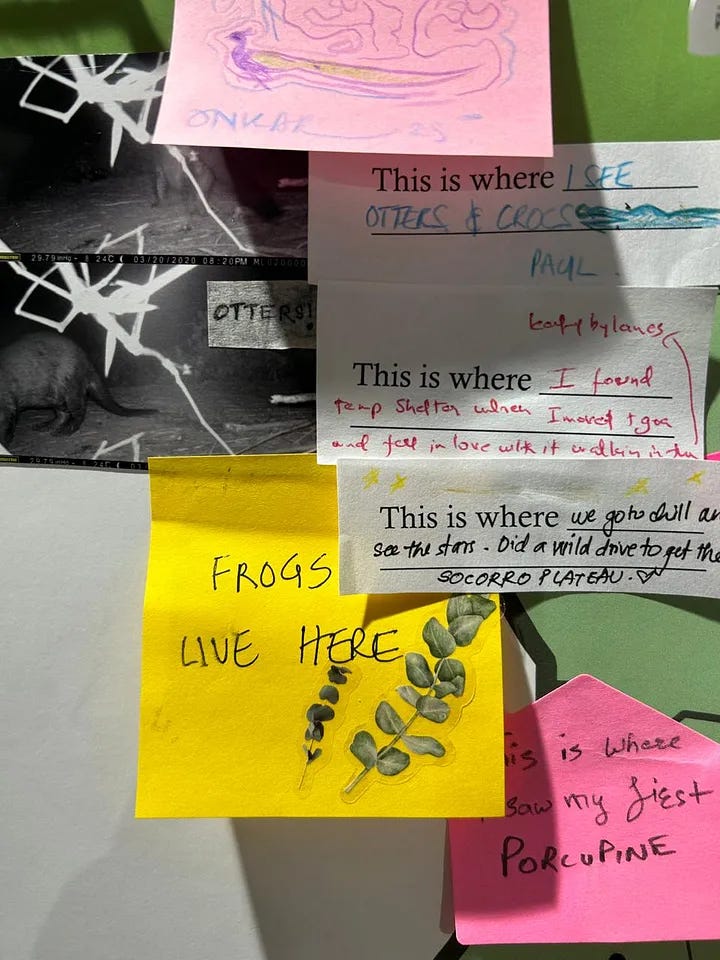

Rhea, in her documentation of the poorly mapped yet all-important Khazans of Goa, a traditional farming system on reclaimed coastal land, is probing into the more-than-human beings missing from considerations of rights and representation of a place. What if we were to follow the perspective of an otter or a crocodile to determine changes in land use? How do they experience the wetland waters?

R: It would be so interesting to consider a multi-species map of a place. How do different species use space? Because when it comes to Khazan’s, concretising a bund means one thing for humans. It makes it easier for us to walk along a stretch of natural beauty or drive across. But for an otter who lives in the pond, a concrete bund is difficult to cross. For a crocodile, that’s impossible to cross. It’s such a different experience for two non-human species that live in the same space, even.

In a way, map-making is all about choices, Nancy reminds me. It’s a subjective exercise. What gets left out? Whose voice is included? Do we zoom in or zoom out? Who decides what the edge of the map really is?

It’s possible then that mapping previously discounted or peripheral narratives, such as the point of view of a crocodile or otter, would lead us to make different choices in localised planning. And operating from a knowledge base that accounts for beings that are as much part of the landscape as people can push us to understand our interconnected reality, and hopefully, prime us to make truly just decisions about how we coexist.

When The Earth Testifies is a knowledge creation effort that seeks to expand the definition of evidence to include strategies and technologies that surface testimonies of the more-than-human world.

Are there methodologies and case studies that you are familiar with / are a part of? Write to us at tammanna.aurora@gmail.com / aditi@agami.in

Edited by: Aditi Kim Karolil and Sachin Malhan