Subject & Witness

How does the Earth's record of memory, presence, and distortion go from being poetic to becoming evidence?

About a time / space

I’m experimenting with a borrowed sound recorder. It’s been a few months. Initially, I wanted to record conversations I was having, at work and with friends, and the general busyness of public spaces. I was curious what a recorder might pick up as ambient sound that surrounds the conversations—birds, sea breeze, static, human movement, mechanical hums, music, distortions, bursts of traffic at a red light—recorded just to remember that I was there that day, at that time.

Over time, I start to listen differently. Not just for good dialogue and rhythm, but also for the absence and presence of things.

In Bhopal, I meet Bhaskar. He reframes sound not just as sensory input but also as valuable data. In soundscape ecology, the study of landscapes through their acoustic relationships, the classification of sound points to three kinds of activity or sources, each providing a distinct layer of information:

Biophony: Sounds of biological creatures such as birds, insects, and animals

Geophony: Nature and atmospheric sounds of wind and water

Anthropophony: Man-made sounds, including those from machines

Layered over time, this kind of sound/data produces a temporal trace, showing how a landscape is changing, or holding steady, or under threat.

Months later, during a SOCH session, Bhaskar shares Bernie Krause’s work with soundscapes from a meadow rich with the sounds of mountain quail, finches, sparrows, and sapsuckers—a site Bernie had been recording in for many years. In 1988, “selective logging” was carried out in the meadow and was said to have no environmental impact. However, field recordings showed that the biophony of the region had dramatically diminished, even though the landscape appeared to be visually unchanged. To show the changes to the landscape hidden in plain sight, Bernie uses spectrograms (also called voiceprints!) to convert the audio into visual markings or etchings, revealing the changes in density and frequency of sound before and after the logging.

This act of separation—of saying, “look, the biophony has dropped here”—alters how we perceive what was once whole.

The research begins here —

What value does contextual, situated information hold in our decision-making process? Do voiceprints such as these ever make it into a courtroom? How does the record of memory, presence, and distortion go from being poetic to becoming evidence?

A fact and circumstance

A recording from an initial public conversation about When The Earth Testifies offers some framework for examining the question of evidence. It was led by Abhay Jain, a lawyer engaged with issues of jal jungle zameen in Madhya Pradesh; Rishika Pardikar, an environmental journalist reporting on climate policy and science; and Rhea Lopez, a researcher, storyteller, and ecologist working with river communities and wildlife.

Unintentionally keeping with the classical structure that legal petitions and arguments in court follow, the conversation begins with a look at the law itself:

Abhay: Whenever we have to present an issue, before any forum, or even before the people, we refer to many kinds of reports and evidence. In the Courts as well, when we take environmental issues, or any other issue, the Evidence Act in most cases defines what will be accepted and admitted in the Court, and what will not be submitted as evidence.

Rishika: The Act says that also? What is not evidence?

Abhay: What is evidence, what is not evidence, what is admissible, not admissible, what is relevant…all these things.

Their exchange lingers as a gentle reminder that the rules of evidence are not straightforward. Section 2(1)(e) of The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 defines evidence as:

In commonly understood terms, evidence refers to a record of happenings—of fact and circumstance. Gathering clues, piecing together what is going on, we do it in our everyday lives too. But when presented before the court, the law lays out strict criteria that need to be met for evidence to be taken on record: evidence must meet the test of relevancy and authenticity, and fulfil procedural requirements to be admissible. The last factor is especially important for digital materials or electronic records, which require an added layer of certification and scrutiny. It’s a high bar—one that helps filter out misrepresentation and frivolous claims—but also one that might exclude many mediums and materials which serve as a record of ecological change.

The sources of information most cited in legal petitions are case laws, expert reports, state records, official notifications, environmental clearances, state-sanctioned studies and research backed by institutions to build a case. The validity and repute of the source carry considerable weight when determining whether a piece of evidence will hold up in cross-examination, and it’s what a lawyer tries to establish through such an approach.

But how we experience day-to-day life is a little different. It’s informed by sentiment and lived reality. It doesn’t always translate into a written document, nor is it always quantifiable, at least not within the common scales of measurement and evaluation we have in place. It doesn’t always follow a fit framework.

One centralised established source may also not always be comprehensive in it’s consideration. Abhay’s work at Zenith, Rhea’s with Veditum, and Rishika’s reports show that the complexity of a natural landscape (and the many ecosystem services it fulfils), how land and wind and water carry geological records, the lived reality of ecological loss, and the voices of those most closely affected are often left out of law and policy.

“Jungle kya hota hai? Who defined it for us? This is information that has been written in textbooks, defined by the government and scientists. But the people who have been living in these places have not tried to define it - in writing - and their ideas have not been accepted when they have tried.”

Below: A choppy edit from the Mela grounds, ambient sound and all.

The questions that come up in this initial conversation (and the many since) examine bias, misrepresentation, power imbalance, and the differing interests and values inherent to decision-making:

How do we look at evidence beyond existing frameworks?

Who gets to create evidence? Who gets to be a witness?

How do we decide what has value? How do we decide what to protect?

The challenge, then, is this: How can legal frameworks expand to take into consideration alternative evidence-building practices that crop up in the absence of or to supplement official records?

The Forest Rights Act, 2006, which permits community elders' testimonies to be submitted as evidence to support a claim for land title, offers some flexibility. In other cases, environmental lawyers and citizen movements find creative ways to bridge the gap:

In the absence of a holistic EIA for the Coastal Road Project in Mumbai, Vanashakti worked with Marine Life of Bombay to index and photograph intertidal marine species living along the rocky shores of Worli. The Marine Biodiversity Report provided the legal basis for raising objections and obtaining a stay order.

Legal submissions by Goa Foundation against three major infrastructure projects in the state were supplemented by representations/appeals by various citizen groups (artists, teachers, scientists, students and others) to save the forests. These open letters were included in the CEC’s report to the Supreme Court.

Himalayan Advocacy Centre monitors and tracks developments in environmental law in the Third Pole region, effectively using RTI as a tool to piece together thousands of scattered government records to establish irrefutability and lay the foundations of a strong case should the need for action/litigation arise.

These attempts are not necessarily outside the scope of traditional evidence, but the approach is intended to meet a different threshold: the artefacts created and information presented make harm visible, place-specific, and real. There are more instances—we are currently studying materials submitted in annexures and exhibits attached to formal petitions to build a repository of such evidence-building strategies and case studies.

There is also the thought that maybe, when the earth testifies, it won’t do so in law’s language, mercenary-like.

If the Earth could speak directly, would it sound like a legal argument — or something else entirely?

When the earth testifies — woh testimony kaise hote hai jab prakriti apne gavaai khud degi? Kya woh scope jo hamare dimag mein bitha diya, kya woh wahi hota, ya phir dharti apni kahaani kuch aur tareeke se sunati?

Yeh context hai - environment ke mamle main, hum kaise evidence ko beyond existing frameworks jo hai - of scientific evidence, reports, legal evidence - jaa kar dekh sakte hai.

When The Earth Testifies

An offering to the imagination from a previous blog post:

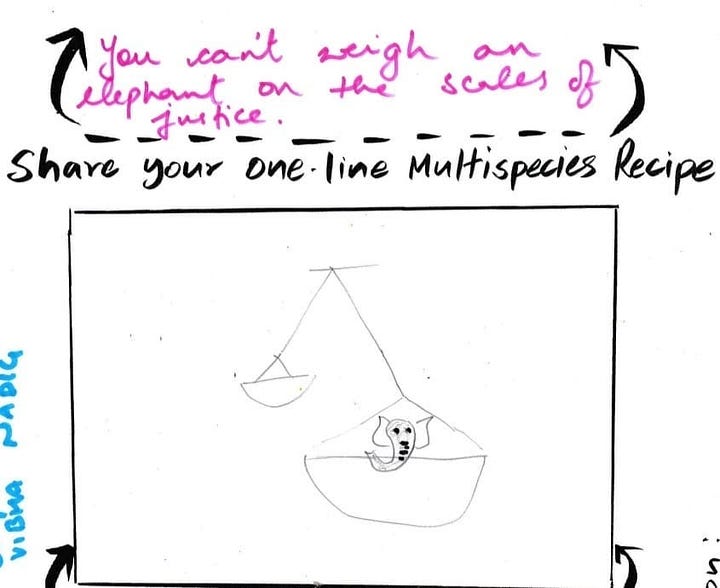

“An elephant’s forest or a river’s estuary is not considered a legitimate venue for justice – those places may be the locus of conflict, but we uproot issues from their ecosystems and squeeze them into marble-floored courtrooms far away.”

This disconnect—between site and hearing, between harm and forum—sits at the heart of our inquiry.

When we remove an environmental issue from the place it unfolds in, we risk losing crucial context. The rhythm of a coastline, the silence of a polluted river, or the conversation of birds interrupted by machinery are all traces of change, and it takes all the senses to perceive or experience these ways in which the Earth records evidence. Legal systems, however, are not always designed to hear this kind of testimony.

There are (rare) moments when courts cross the distance — visiting sites or asking for a ground report, appointing amicus curiae, or setting up a committee to investigate and advise in specific instances.

More often than not, it is songs, stories, maps, species lists, open letters, and other ground-truthing methods that the law must rely upon to piece together the fragments of ecological change in a way that conventional formats may not. To tell a complete story. To reintroduce site as both subject and witness.

I am reminded of a play I watched years ago, a courtroom drama titled Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness. In a staged hearing, artists present sound, image, and story to demonstrate ecological and cultural loss, challenging the state’s purely economic rationale for a river linking project. Though the acting Judge ultimately rules against the artists, he acknowledges the legitimacy of their approach: that artwork, especially when created in collaboration with affected communities, can carry evidentiary value, and that artists, too, are equal stakeholders in policy-making, as much as economists, scientists, lawyers, and others.

The fictional courtroom raises some real questions: How do we value a way of seeing? What happens when ways of knowing that are visual, oral, and embodied enter a space governed by forms and legal codes?

In our research, Aditi and I are looking at legal strategies and evidentiary practices to find answers to some of these questions, and learning from those engaged with law, science, and art for an interconnected approach.

When The Earth Testifies seeks to expand the definition of evidence to include citizen science data, counter-mapping, soundscapes, and other existing or potential documents of changing climate conditions and environmental justice concerns. We wanted to share an early look at our ongoing exploration and invite you to contribute with different methodologies and case studies that you are a part of / that you are familiar with.

Write to us at tammanna.aurora@gmail.com / aditi@agami.in

Coming up next

> An evidence 101 learning circle with an environmental lawyer. RSVP for more details.

> In the next issue, Aditi and Labonie document the mapping of community forest rights in Bastar.

0.1 ignorance (certainty that you don't know)

1 found anecdote (assumed motive)

2 adversarial anecdote (presumes inaccurate communication motive)

3 collaborative anecdote (presumes accurate communication motive)

4 experience of (possible illusion or delusion)

5 ground truth (consensus Reality)

6 occupational reality (verified pragmatism)

7 professional consensus (context specific expertise, best practice)

8 science (rigorous replication)

<- empirical probability / logical necessity ->

9 math, logic, Spiritual Geometry (semantic, absolute)

10 experience qua experience (you are definitely sensing this)

Anecdote can provide evidence, but only barely, as a tiebreaker.