Mycelium as method and Justice as question

Bharati Challa reflects on her experience of the Goa edition of the Multispecies Canvas

What is possible for Goa if justice were not just a human project? We had a day to ask, listen, and probe that question at the Goa Multispecies Canvas. Could legal processes learn to register absence, song, ritual; could a petition carry the cadence of a folk song and the memory of fifteen plants used in a puja? The Canvas as a wager and a map; can justice learn to hear a song, a ritual, an absence? If so, where and how might it listen?

Landing, Wandering, Stumbling

I came to Goa with no plan beyond a friend and a Sunday gathering. We had promised ourselves no scooters this time - only buses, lifts from friends and our own feet. The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot, we repeated. I landed a day early and let my shoes take charge in Fontainhas, where our hostel dorm opened into the narrow Latin Quarter. It was September, the monsoon tapering off. I carried an umbrella from Hyderabad and set off wandering. Two bakeries and three pasteis de nata later, I stumbled into the Charles Correa Foundation.

As I wrote in this week’s Praani dispatch1, Correa’s notes weren’t about buildings so much as relations. He wrote about courtyards open to the sky, wells drawing from aquifers, and maidans alive with birds. He called them “non-buildings,” fields of relation rather than structures. To stand under a parasol roof or walk across a shaded corridor was, for him, already to be in conversation with weather, soil, water. I didn’t know then that the Canvas would return me to this intuition again and again - that everything is already entangled with everything else, like roots and fungi under the soil, unseen but shaping what grows above.

Sunday began with the drive to Salvador do Mundo, past the landscape of the city into Khazan lands. The venue, Sensible Earth, sat right on their edge. It mattered that we were here and not in some clinical seminar hall. A reminder of the skin in the game, putting the conversation literally at the contested edge.

By the time we arrived, Aditi (Agami), Tammanna (founder, temp.mag), Joanna (Circlewallas and Act for Goa), Smriti (Socratus Collective Wisdom Corporation) and Sanjiv (founder, Sensible Earth and Maka Naka Plastics) were already setting up. It felt like walking into a kitchen where everyone was already cooking, conversations simmering, waiting for new voices to stir the pot.

A Gathering is a Dare

It was Tammanna who opened the day. She set the premise for why this strange, passionate and alive admixture of lawyers, conservationists, ecologists, artists, and those who refused these labels had gathered on a Sunday (and Goans take their Sundays very seriously!).

The ‘Canvas’ is both a map and a dare. A map, because it forces us to lay bare the hidden scaffolding of justice: who gets counted as subject, what gets named as harm, and where justice is even imagined to take place. And a dare, because it asked us to redraw those lines from a multispecies perspective, to risk seeing law as something porous, leaky, alive. In practice, the Canvas gets us to gather to walk the routes it draws and to test them on the ground. Which small, administrable changes will shift the calculus first?

Aditi followed, offering poetry - lines from a poem by conservationist Gabriella D’Cruz, who wrote of Goa as blood and bone:

your body extends into the landscape,

your blood contains the salt of the sea.

It folds land, river, jackal, soil, and self into one continuity. Not just entanglement, which still assumes two separate threads, but extension, where one body runs into another. That line would stay with me all day, resurfacing in every conversation like a tide pulling us back to the same shore.

Then Smriti spoke. She reminded us that the problems we were here to wrestle with are ‘wicked’: tangled, systemic, unsolvable by linear fixes. But collective wisdom does exist - in the room, in the lived knowledge of farmers, scientists, activists, artists. How might these ideas be prototyped, tested, made real?

Who Would You Be If You Weren’t You?

Introductions arrived sideways. Rather than jobs, titles or degrees, we offered intent and kin. What brought us here, and what non-human entity would we be for a day? Nester, a marine biologist, began with: “I always think about this prompt.” I tried not to show how much that stunned me - the idea of always carrying, in the back of your mind, which non-human being you might wish to inhabit. In my sterile world of bare acts and corporate law machinery, animals show up only as menace: the “monkey menace” on campus, never just monkey. Nester chose the sea turtle.

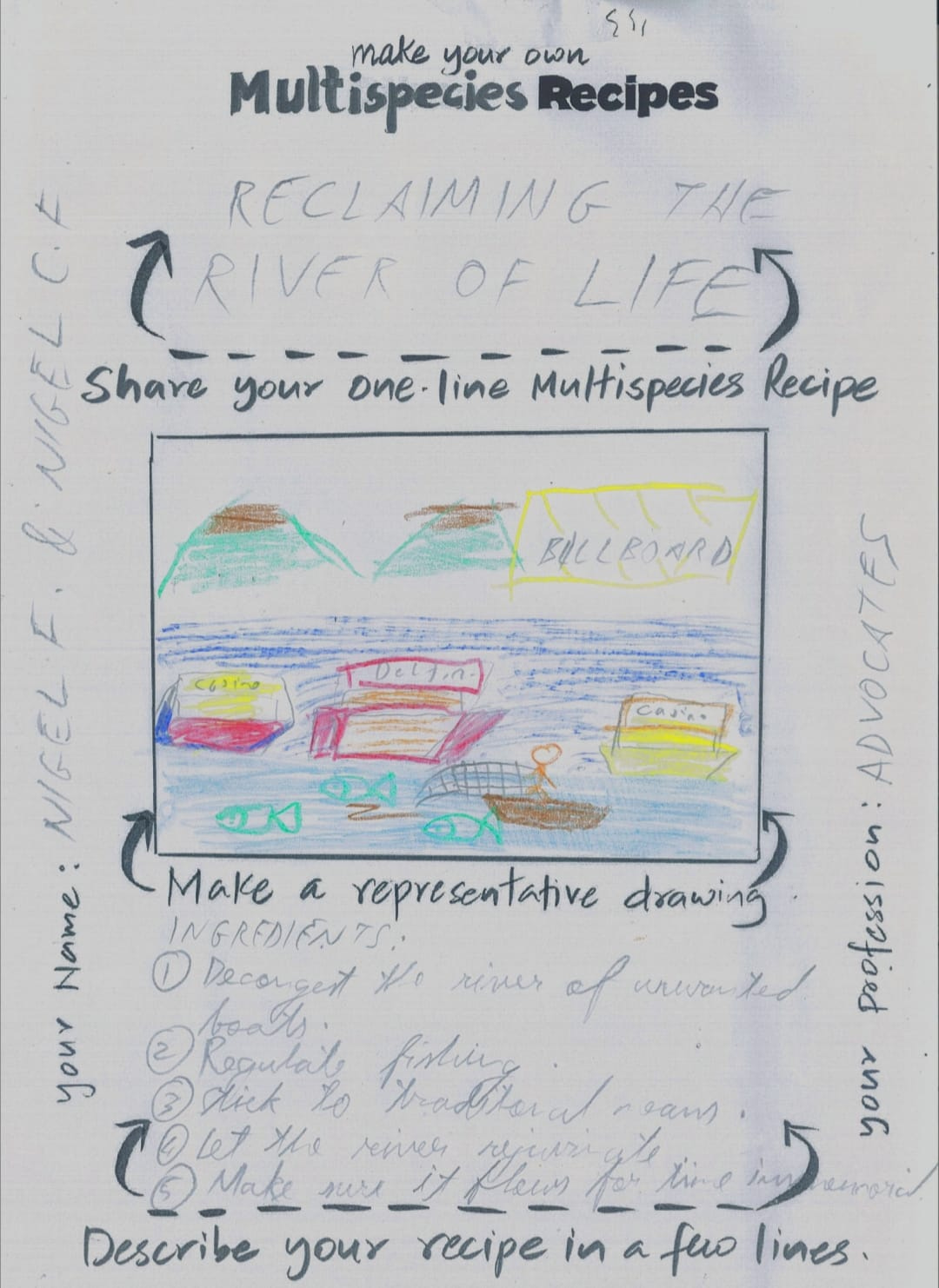

There were also birds (Tammanna and Sanjiv choosing eagles, Joanna a Brahminy Kite), soil and forest beings (Malisa choosing mushrooms, Nishitha wanting to be a banyan), and the cohabitants of our streets (Nigel’s crow, Rui’s beach dog). Mycelium, for its connectivity, kept recurring2. Different bodies, different tempos, the same knot of care. The air shifted with each answer, the human centre loosening its grip.

The Body Writes Too

After the introductions, Joanna invited us into our bodies, to reach into other-than-cerebral intelligences in our bodies. We were asked to read case studies, or if something more personal pressed on us, to draw from that. Each of us was invited to tell our stories, to feel and sense what spoke to us with our non-thinking selves. And then - release! What does it feel like to be unstuck? Where in our bodies do these feelings lodge themselves? A heaviness in the chest? An urge to feel mud and not kadapa stone underneath oneself?3

By lunch, the spell had loosened into chatter. The meal was sattvic: moringa bhaji, rava fry, local rice, barnyard millet payasam. Plates moved and conversations braided: lawyers, conservationists, artists, shoulder to shoulder.4

I thought of mycelium again: unseen, networked, moving nutrients between trees. Who knows what fruit these conversations might bear in weeks or years or decades? For now, it was enough that they were happening. What mattered was that the threads had been woven and kindred spirits had been recognized. Here I am in this space. Here you are in this space.

After lunch, Malisa, a practising lawyer, observed: “We were all really saying the same things.” Someone spoke of the sense of collapse that working in the non-governmental sector can bring. How does one then maintain a sense of mooring and optimism without slipping into cynicism? One answer: we have a choice in how much we lean into and draw from our camaraderie and oneness as mammals. Life wants to survive, someone else nodded. There is momentum. We’re surrounded by people who are all feeling just as much and just as intensely about these things.

What is Possible for Goa?

Talk widened. Someone suggested a digital archive of Goa Foundation’s forty years of litigation - archiving itself can be a political act, especially in law, where memory is guarded by moat and hierarchy. Others spoke of rethinking process - open letters, of soundscape ecology, of the way collective action had pulsed through the Amche Mollem movement.

Nigel CF asked the elemental question of how we might get the law to register absence, circumscribed as law’s vocabulary is by sterile statute books. Pointing to the DLF Project in Nerul (that is visible from the High Court compound), the subject matter of an ongoing litigation: “A verdant green hill now fully brown. Nobody knows how many trees there were. Can I ask the judge to step outside and look?”5

Malisa spoke of how judges read their morning paper, too. Protests and public pressure - visible, reported - shape outcomes as much as pleadings do. The public presence of a claim converts it from a specialist’s complaint into a citizen’s wound. I recalled Gabriella’s poem in that moment - “I know whatever happens to the land and sea, also happens to me”.

Can a Judge Hear a Song?

Ideas kept tumbling: citizen science, resource-mapping, geo-tagging, satellite mapping, and the use of community datasets in PILs. Their success. We came back again to the knowledge that everything is everything. A PIL that has been drafted collectively by lawyers, villagers, ecologists, and residents is far more compelling purely due to its primariness. I also wondered about the sense of agency one who is not a lawyer might feel over the PIL and the issue itself, if the PIL was treated as more than just a lawyer’s document. All of us have stakes, and all of us are lending spokes to the wheels of change. Multi-drafters!

Otherwise, all the trappings of an unfruitful conversation: different, disparate language that the other does not understand, creep in. Sound out the sighs of sand dunes being mined, as against the christening of each sentence in pleadings with “it is humbly prayed that” - even when it is hardly humble; even when it is hardly a prayer at all. Can each of their intonations and inflections make the others’ mind, memory or heart sing? I was told justice was meant to be a dialogue. How do you speak to one who cannot hear you? How do you listen to one who does not compel your ears to pick up on frequencies you are not attuned to?

Sabina and Nigel said, “It cannot always be a Goa Foundation” - we ought to be the ones we have been waiting for. Sanjiv, who had been listening quietly, broke in to say that Goa has one of the highest numbers of activists per capita in India. We must find paths of least resistance - even, and especially, the small victories matter. Bring more young people into the fight, or else the struggle itself grows old.

Questions were put to the lawyers about the technicalities of litigating. It was clear to me that, suddenly again, something had shifted in the room, and the barrier of semantic and legal typologies had reared its ugly head again. Suddenly, we were back inside the fortress of legal language: “jurisdiction,” “maintainability,” “affidavit”. The same people who had spoken as butterflies, fungi, and banyan trees now sat silent, as if the conversation had slipped out of their reach. This was the tyranny of legal typologies in that it turned even allies into spectators. Can the master’s tools ever dismantle the master’s house?

Outside, the Khazan lands held the last of the afternoon light. The marshes did not care for affidavits or petitions; they answered only to tide and season. The Canvas itself had gone to spore, and metaphor was now also method; threading through the day, surfacing in introductions, in stories, in the way lunch had turned into community. The Canvas itself had become fungal: a living artefact carrying spores from one place to another, breaking down what is rigid, seeding what is possible.

Bharati is a 4th-year law student at NALSAR and an intern at Agami’s Praani initiative. She’s asking what it means to practice law in a world where firms stock six types of artisanal coffee while undertrials wait decades for court dates - and whether the tools built by that system can ever address the questions it refuses to hear. She writes from that gap, trying to figure out what grows there.

Praani is a (mostly weekly) newsletter by Agami on listening better to the voice of nature, ways of amplifying them, and finding pathways to bring them into our ways of governance. Please write to me at bharati@agami.in if you’d like to be part of the mailing list and are unable to join using the hyperlink above!

By the third mycelium, I half-expected the floor to sprout mushrooms. Patterns repeat until they announce themselves as truth: connection with each other and the Earth, with all its beings and non-beings, is what we are all starved for.

Sometimes the revolution is just unclenching your jaw. Law trains the head; this exercise asked what the chest and gut might legislate if given the chance.

Filaments cross more easily over rice than over petitions.

The law resists looking out the window, because outside lies everything it cannot contain.