What is it about an Elephant? | Note #6, Praani

'We are in kindergarten, sounding out our first words'

Praani ki Kahani

Praani is a note by Agami on listening better to the voice of nature, ways of amplifying them, and finding pathways to bring them into our ways of governance. At Agami, we are deeply interested in how rivers, forests, animals, and even the winds and the stones, might speak into our deliberations on justice.

[This Note had originally gone out on August 27th, 2025]

Offering For the Week

What is it about an Elephant?

What is it about an elephant? Most of us meet the elephant in headlines, in human–elephant conflict and crop raids, or as an unwilling mascot in the cute economy. But we must pause and ask: what is it about an elephant, and what can the elephant teach us, and by extension, our human-made justice systems? Elephants carry thick, complex inner lives, with memory and conscious choice, with practices of grief. We are only beginning to learn this. As one researcher put it, we are in kindergarten, sounding out our first words.

There is an old legend of Pālakāpya, a young sage raised among elephants, tending their wounds, reading their moods. One season a king ordered elephants be trapped for the safety of the people of the kingdom. Palakapya on hearing this went to him to make an appeal for the elephants’ release. At the heart of his appeal sat a plain truth: elephants are wild, and the wild must be allowed to remain wild. This is the paradox we inherit, and, by extension, so do our justice systems. To preserve the wild is the oxymoron of our times.

Notes from the Field

How might we preserve the Wild?

How do we begin to grapple, and to negotiate, with this oxymoron of preserving the wild? For this, we worked with Dr. Nishant Srinivasaiah on a learning circle held in Mumbai last week. One of the most urgent answers that emerged is that our justice systems very easily understand a language of captivity, or rather, a language of protection contingent on captivity but struggles to make sense of a language of protection founded on freedom.

Through the day, Nishant took us through the social, biological, vocal, and affective lives of the elephants he works with. What emerged at the outset was that this was not a relationship where he goes to the field to merely document elephants in rigid scientific terms and parse through existing methodologies; it is akin to an other-than-human collaboration with elephants, a collective attempt to share the joys and grief of being an elephant.

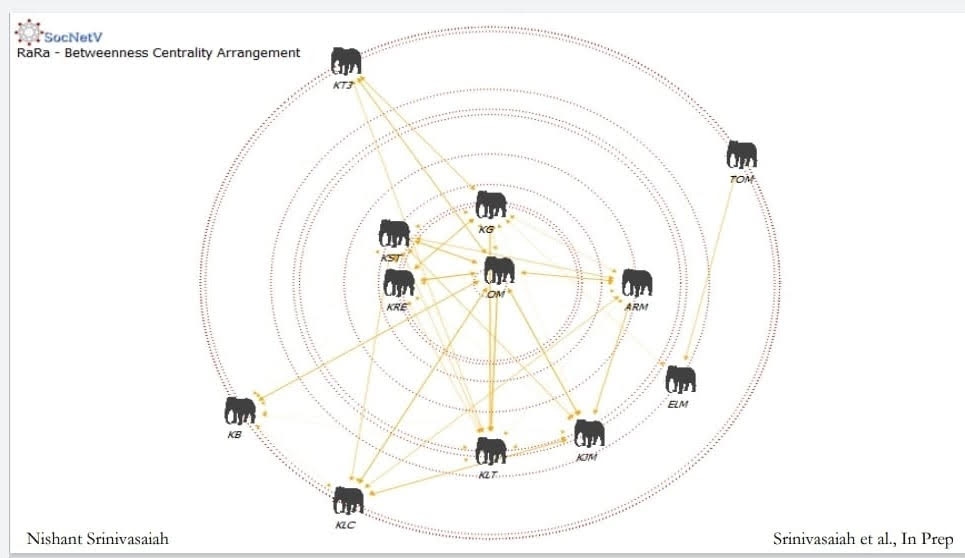

He grounded the discussion in parts of Nussbaum’s capabilities approach in the context of animals, and then stayed with one powerful interplay: the social life and the biological life of an elephant. In many ways, elephant populations form rich social worlds and cosmologies around an influential elephant at the centre. A language of captivity, or existing frameworks of protection, often remove that central elephant, which can mean brutally shaking, if not destroying, a social system cultivated carefully over decades. So while existing systems of justice preserve the biological life of the elephant, they cause an ecological death, because a huge chain of relationships, intersections, and entanglements is torn by approaches of captivity.

Elephanthood, a story of life beyond law

So, what is it about an elephant? What must we learn from the elephant when we think about our systems of justice?

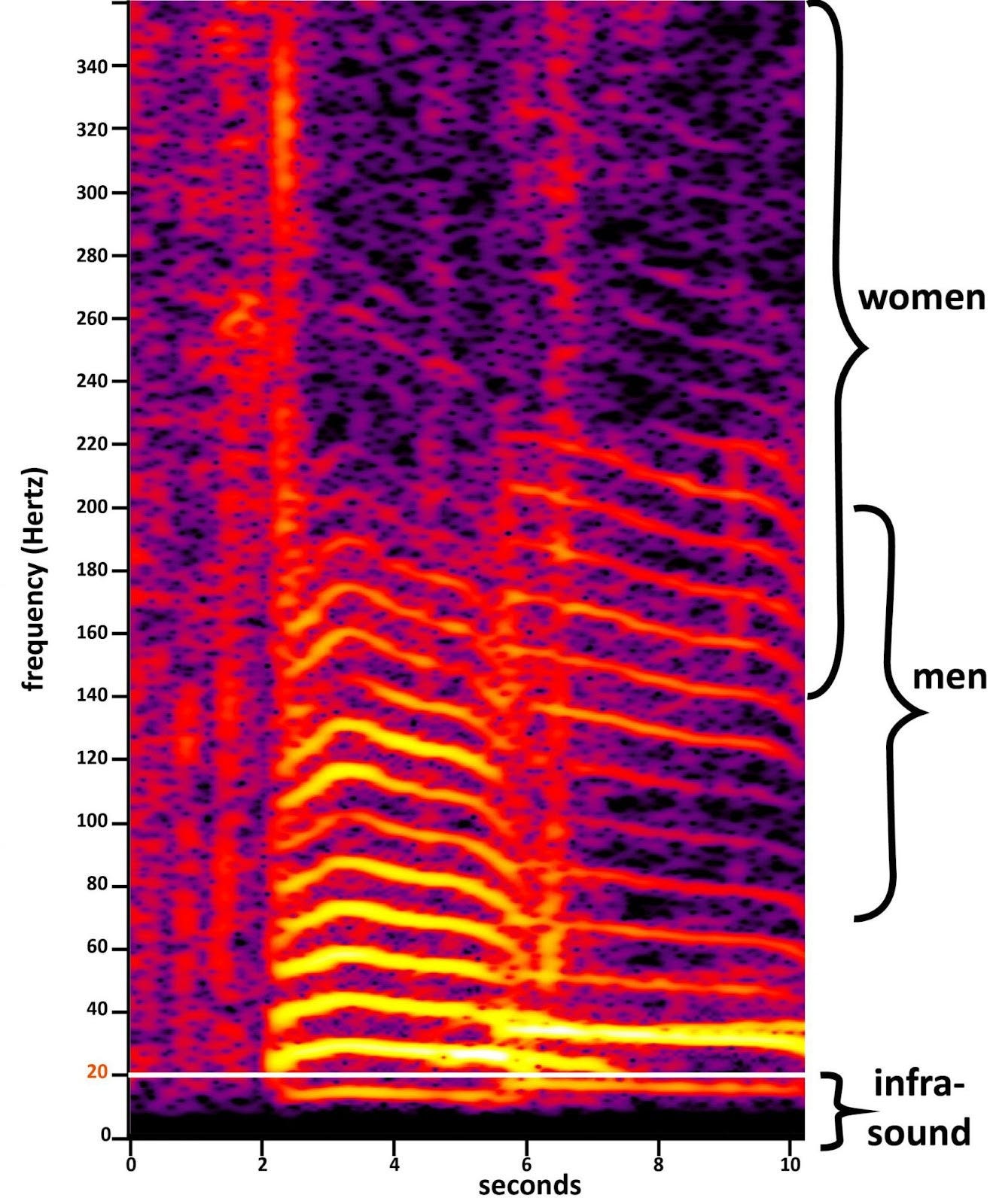

A bedrock of our systems of justice is personhood, the idea that questions of life, liberty, equality, freedom sit with the person at the centre. Often this rests on a vaunted sense of human uniqueness, on assumptions that our consciousness and our sentience must sit atop. It tempts us to believe we are, in some ways, bigger than the elephant, our CV of capacities longer than an elephants’ memory. But as Nishant showed, elephants hold powers we barely register, one such being the ability to speak infrasound (Hear it here), in low, pulsing rumbles our ears cannot begin to hear. But we must listen to what the elephant is saying. We must begin to think in terms of what Nishant calls elephanthood and ask what changes in our notions of personhood when the stories of elephanthood enter. Ask what then shifts in our systems of justice.

For this, we could start thinking in terms of a trialectic, as Nishant documents in his work: the material and physical sites where elephants reside; how the elephant is imagined and represented in our modern sites of imagination like the city, the media and the legal system; and, most critically, the lived, everyday practices, negotiations, and behaviour of the elephants themselves. Perhaps, a more democratic language can emerge from here. This is Nishant’s quiet dream of a better world and a justice system in which he does not have to be an interlocutor for the elephant in the room.