What is Essential is Invisible to the Eye

A scribe’s documentation of Agamishaala United | Bhopal, 2024

The Context

Every year since 2021, Agami has hosted a reunion of past Agamishaala members - Agamishaala United - right before our annual field convening. In 2024, this took place in Bhopal, 2 days before the Justicemakers Mela.

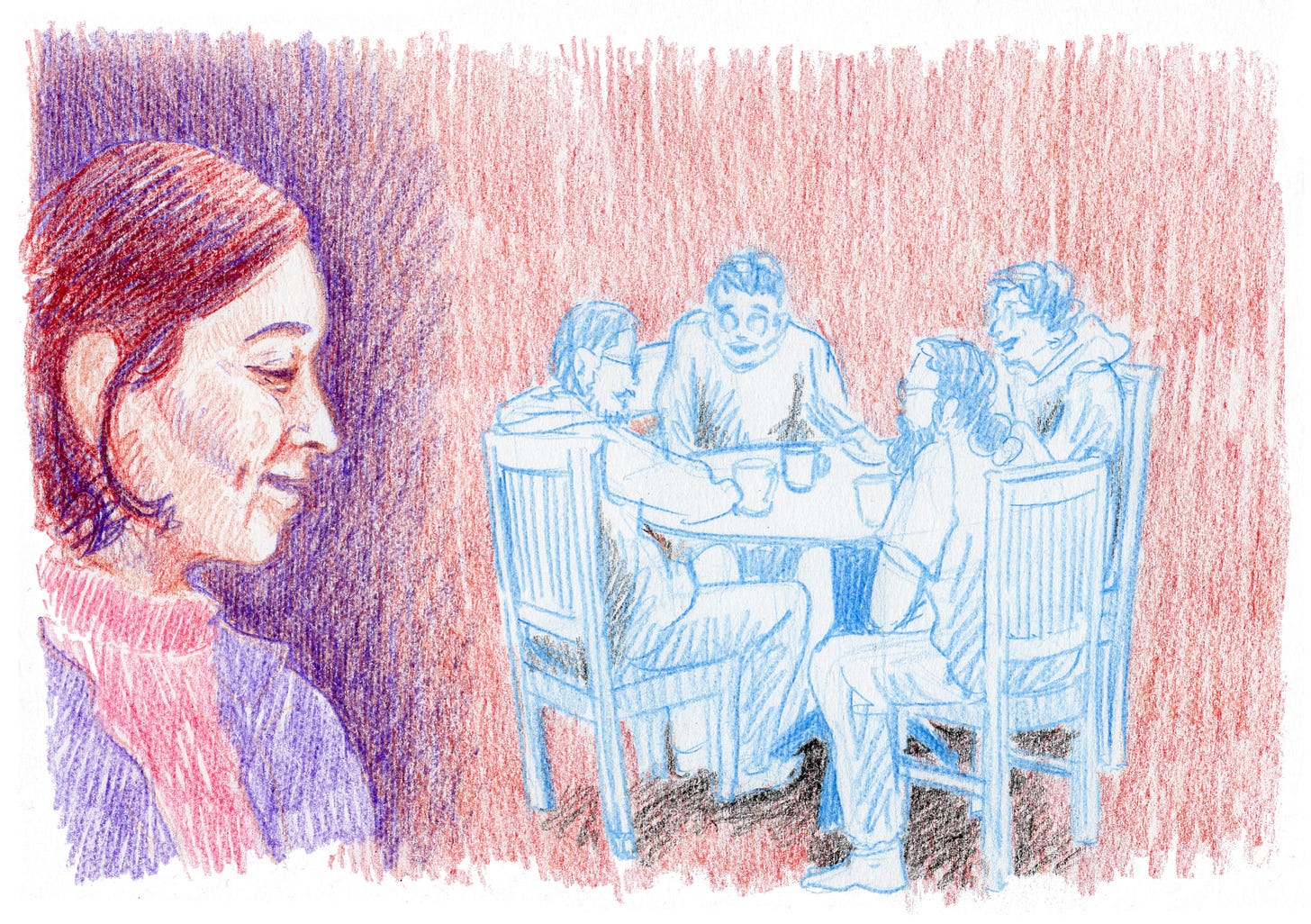

In an attempt to capture and learn from what emerges when a group of Justicemakers get together in a space like this, we once again invited roeqin, an artist and arts-educator, to scribe what he sensed and witnessed.

Foreword

I attended this year’s Agamishaala United to observe us and the ways in which our learnings emerge from this experience—That is my role as a scribe. But beyond this role, there is a deep sense of belonging to this community and a genuine curiosity to see how these experiences shape us and our work. I have myself experienced the growth that spaces like this can induce within people, having begun my own Shaala journey in 2023. Agamishaala is a community within itself, with its own shared vocabulary, and so my language of documentation tends to take the tone of an insider. But i* will try, to the best of my ability, to open this world out to readers who aren’t acquainted with the Shaala.

In my scribe documentation, this time, i was keen to deliberate on our experience at Agamishaala United with Artika, Manish and Aditi—the quiet, ever moving cogs behind the Shaala, who have had these 2 days in their consideration for many months prior and many more months after. I met them a few weeks after our gathering in Bhopal. By this time we had all made our way back to our respective homes, and we had to converse through the little rectangular windows of a video call, although in an ideal scenario, we should have been having this conversation in a park somewhere, sitting in a small plot of green, a canopy of leaves and branches overhead. The conversation we had that afternoon was extremely heartening. It was possibly the first time that i had heard them talk about the Shaala so candidly.

As much as i might draw out a semblance of meaning from my own experience, i’d want to refrain from assuming that it is a shared understanding, to force a meaning out of these experiences that serves the entire group. The learnings we take away from Shaala are like clouds on a bright, windless day. The shapes slowly change, meet and diverge, become wispy, all the while moving ever so slowly in a particular direction. The shapes they make speak differently to everyone—the meaning is for the observer to make. I’d want this scribe documentation to just provide glimpses into this shared space that was held for us, and that we held together, to open the opportunity for these learnings to make themselves felt even if not fully understood.

~ roeqin

*The uncapitalised ‘i’ has been deliberately used since the ‘I’, as stipulated by English grammar, feels too egotistical to my liking.

What is essential is invisible to the eye

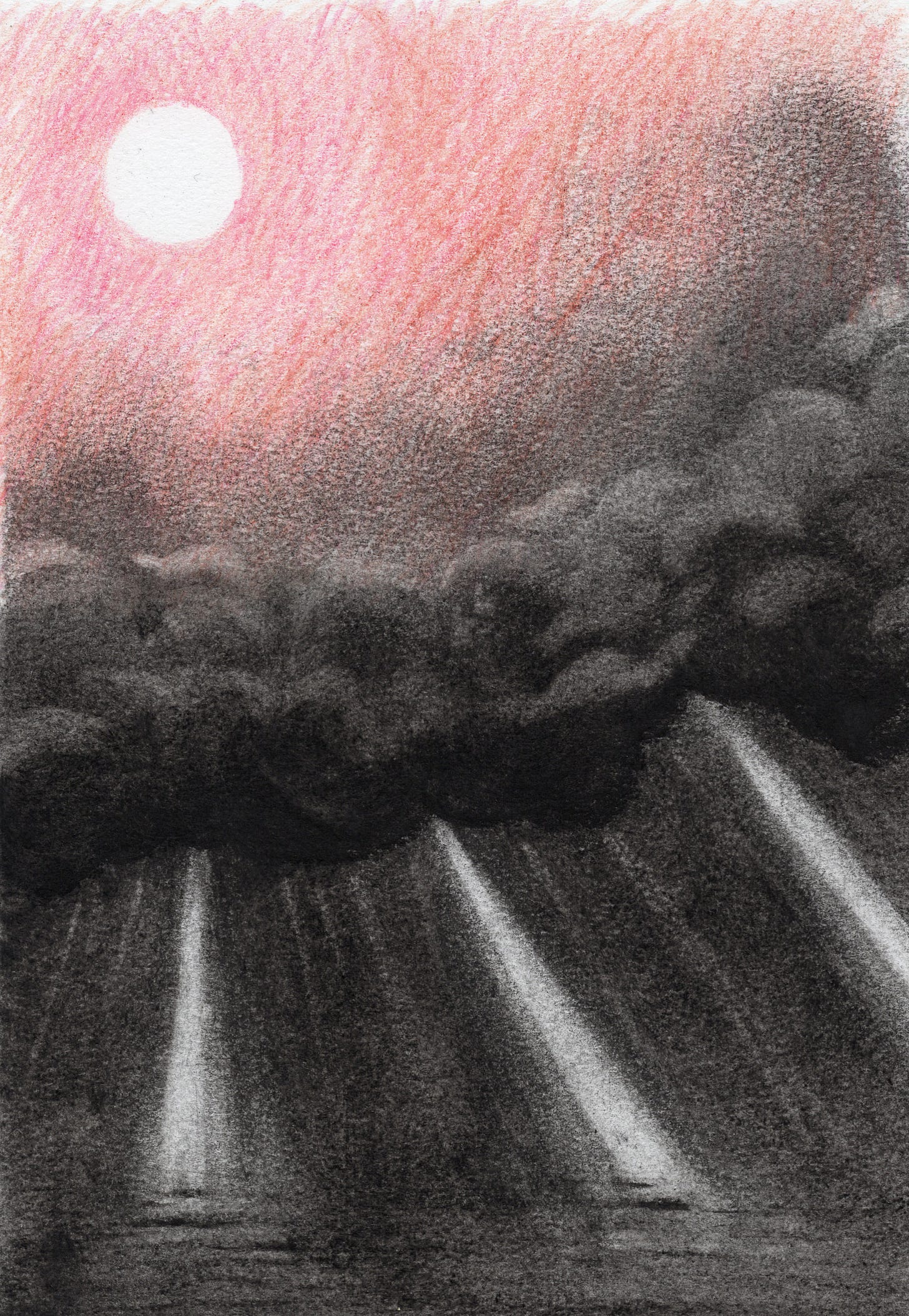

“What did those moments of doubt look like to you?”

“It’s the other way around—there is a large cloud of doubt and then the sun shines

through and you have clarity, and you keep moving with that clarity…”

“And clarity? What about moments of clarity?”

“There is clarity about the process, that is the light that shines through.

The sun didn't make an effort to hide. Stuff came up and obscured it, but it is always there.”

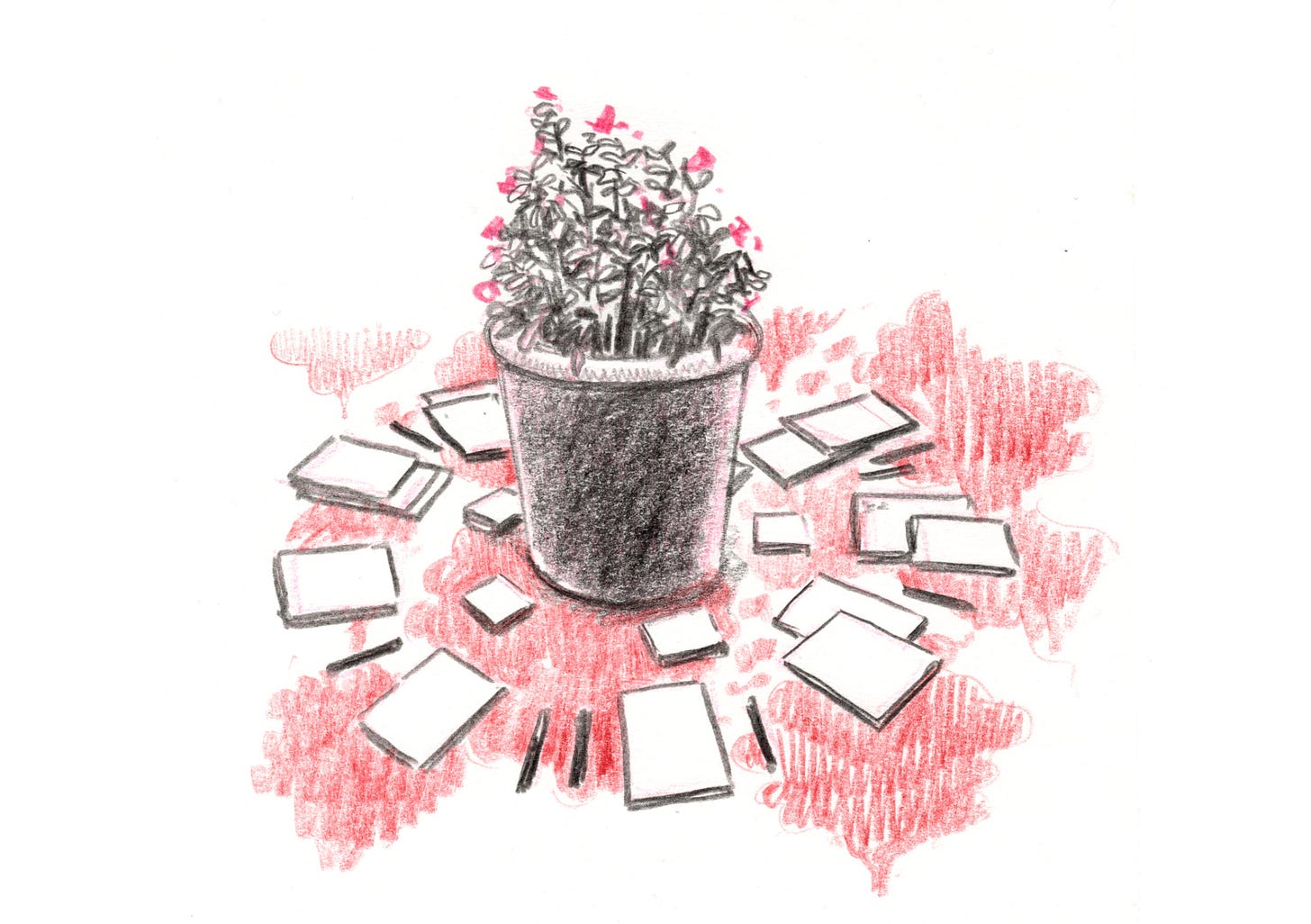

The metaphor of the container is deeply embedded within the culture of Shaala. The practice of building a good container, or rather, being a good container, is one that the Shaala, its people, and its moulders are well acquainted with. The container holds, it unifies, it enables. Anything that is held within the container finds an acceptance and a closeness to everything else that lies within it. And those of us that have the opportunity of being held by the container carry an intangible impression of it, one that holds this community of Agamishaala together.

And yet, the container is not impervious to the feelings of doubt. Rather, it is equally shaped by it.

Artika: “Our job is to create the right container, those enabling conditions in which different kinds of things can grow and flourish. I guess it comes with its own doubt, but the clarity I have is in the fact that this work is critical in what it makes possible.”

* 20 minute dance is one of the many Social Presencing Theatre practices that we are introduced to in the course of Agamishaala, derived from the Presencing Institute (MIT, USA).

When i asked them to give me metaphors that might represent the Shaala, both Aditi and Manish imagined different kinds of containers—

Aditi: “You know when there is a water canister or a matka, with a tap, there is usually a container kept below it to collect the water that trickles out so that it doesn’t go waste. It is actually the care in that act, to hold something precious, which I think is a metaphor for Shaala.”

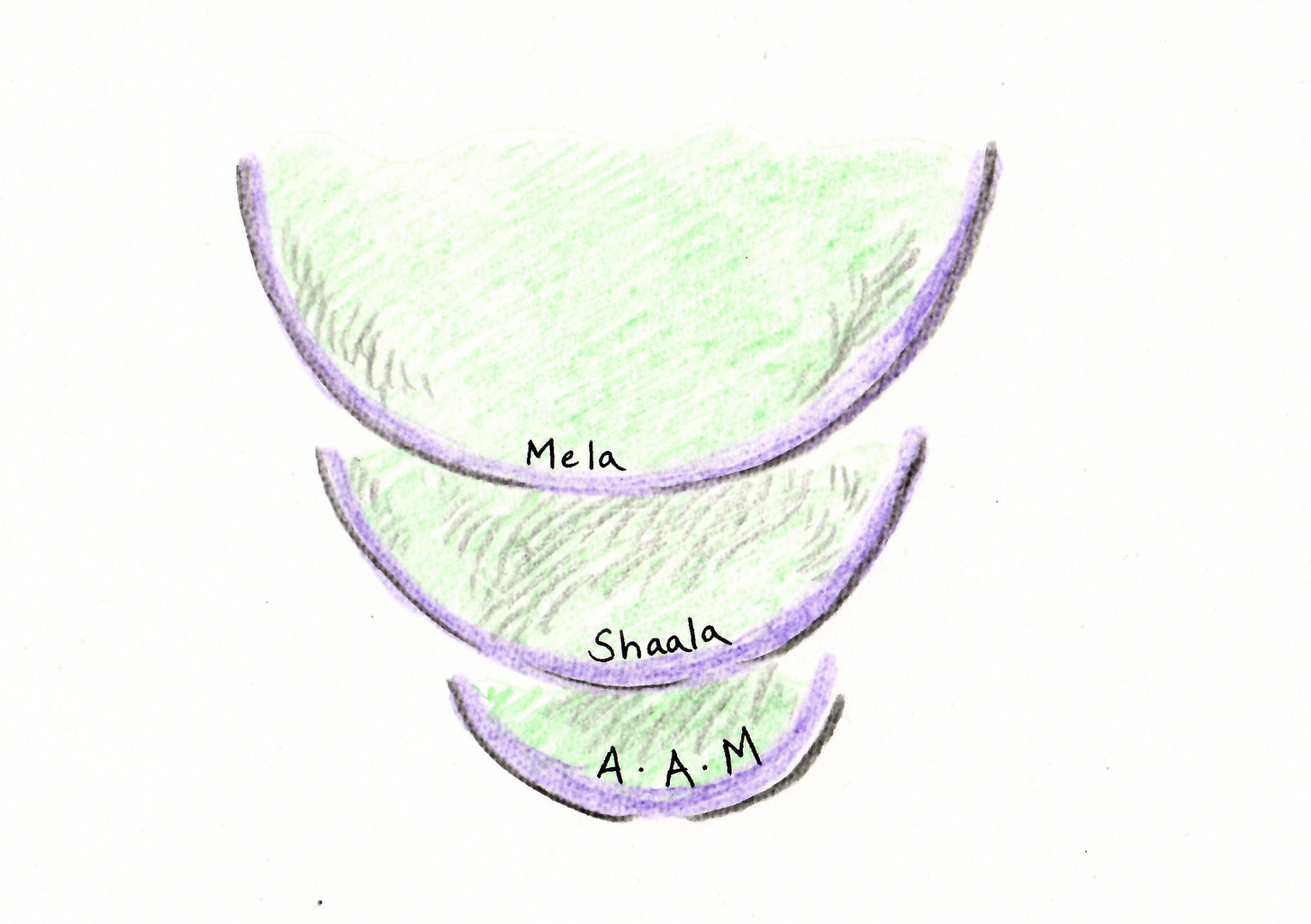

Manish depicted a nested container in a diagram.

Manish: “There are so many containers. The three of us contain the Shaala, the Shaala contains the Justicemakers Mela. it is a container within a container within a container. It looks so unstable! But it is also so beautiful.”

I sense this container every time i step into a gathering of Shaala members, like an echo in a closed space that hangs in the air. Even as it engulfs the senses in its vastness, it signifies the presence of a container, the walls that hold the sound within. If one has to trace that feeling of belonging that resonates through the people that are a part of this space, it leads back to the three of them who create this space for us. The container, even when it tries to remain invisible, is felt in every reverberation.

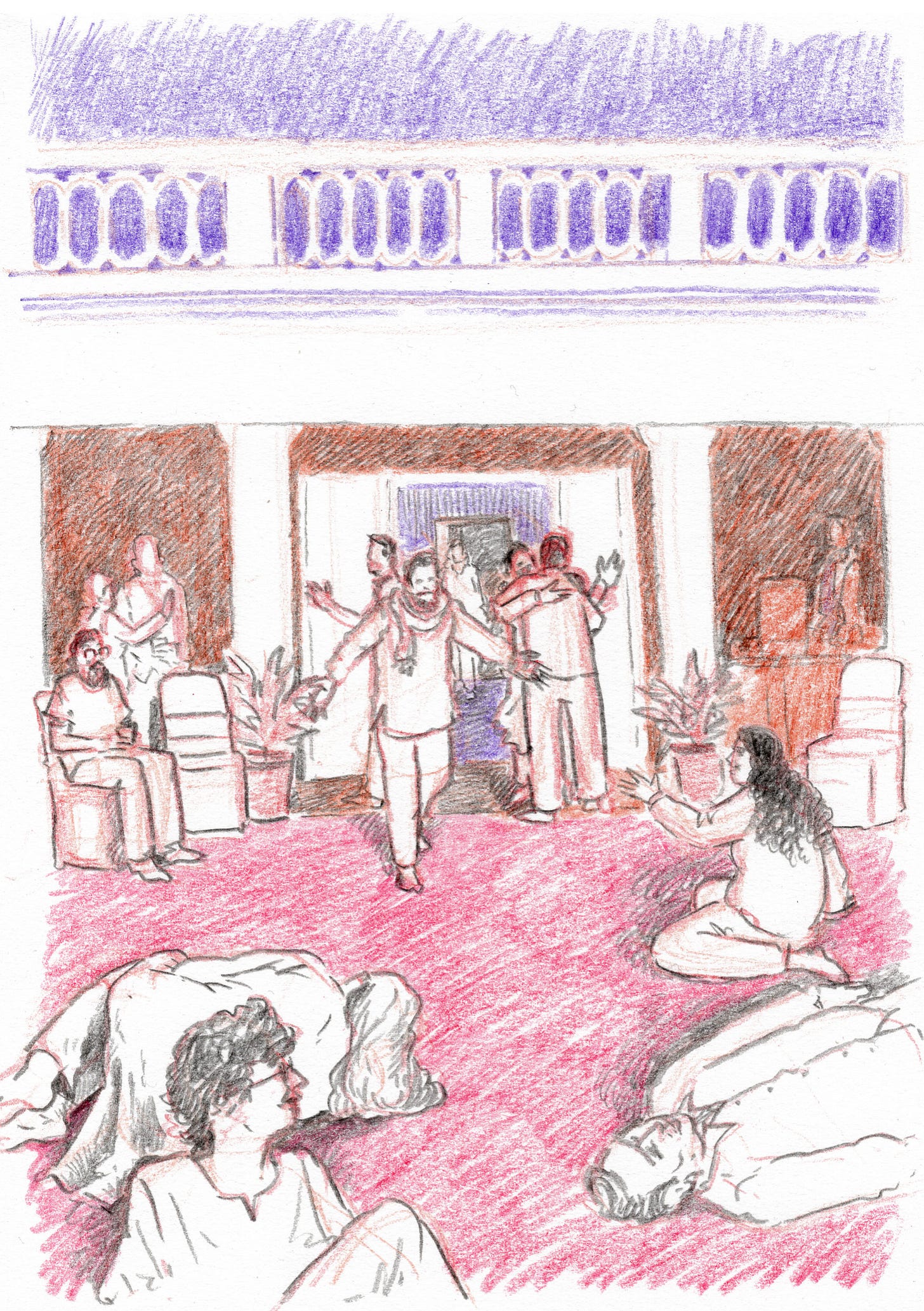

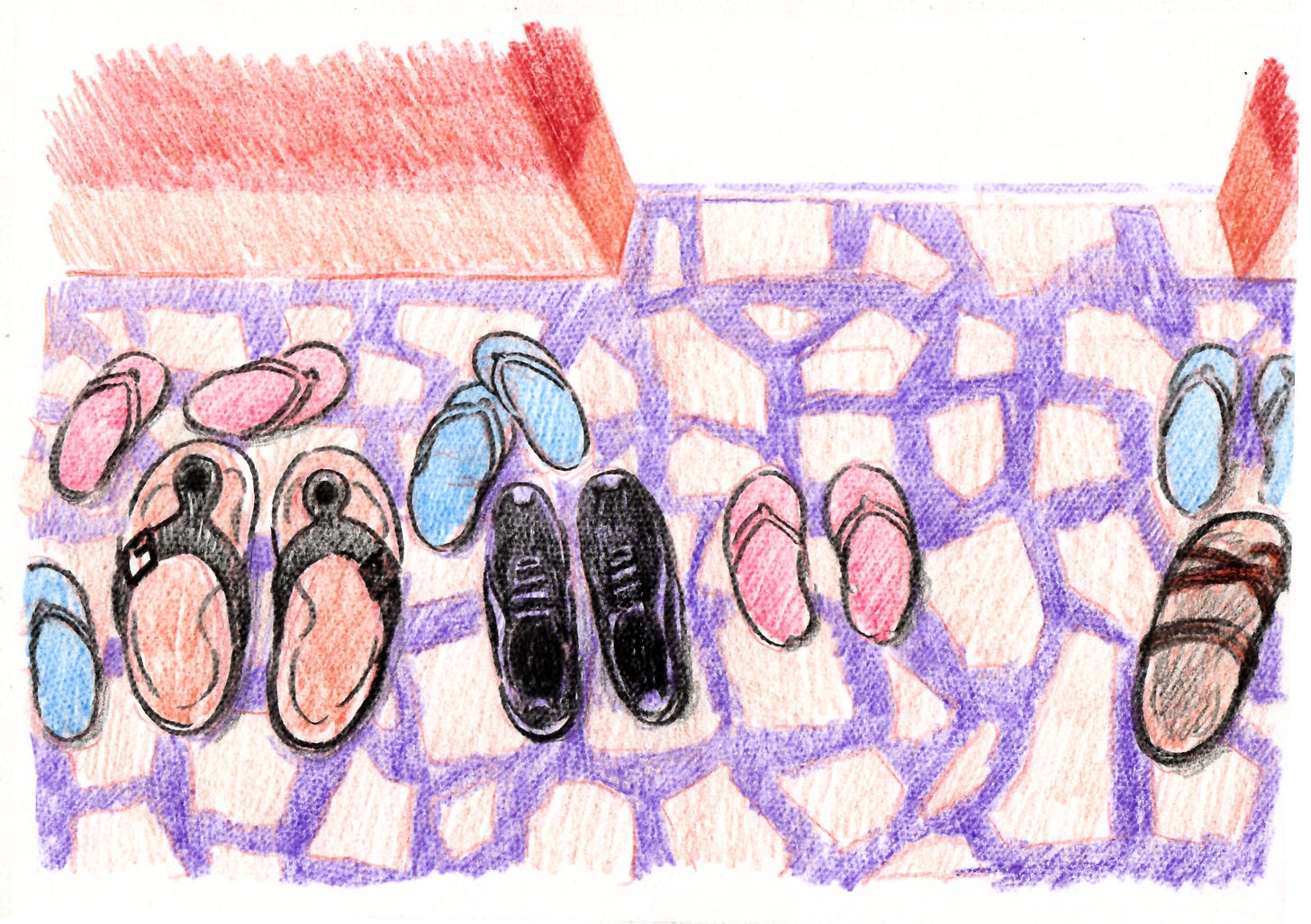

We met in Bhopal for a little less than 2 days. Thinking back, it feels like a blur—it was over, just as i had begun to settle in. It is such a small window of time, and yet these 2 days offer so much to each of us. For some it means rest, for others it is an opportunity to meet their friends and companions, yet for others it is an attempt to seek answers—we all come together carrying so many different intentions. Some of us find what we are seeking, others find directions to pursue in search of what they seek. There were so many people that i hadn’t seen in ages, so many that i would be meeting for the first time. Stepping into the venue, i could sense hesitation within me, maybe even nervousness. I walked through the huge glass doors, and as i made my way to my room, i kept meeting friends at every turn, my progress halted with smiles and hugs, pats on the back and polite pleasantries. I sensed the knots untying as i gave in to the embraces.

I found myself sitting with Hameeda and Lubhyathi a little while later, all three of us having met in person for the first time since our Shaala in Ranikhet. I had heard that Hameeda wasn’t feeling well, and was immediately reminded of her disappearance through our last day at Ranikhet under similar circumstances. I said “यार, तेरेको हर बार कुछ ना कुछ होता ही है !”, and she laughed. A sudden wave of comfort and familiarity washed over me, a reconnection with the intimacy we had felt in Ranikhet with every member of that cohort. I sensed that i had truly arrived.

It is understandable why all of us look forward to these occasions that Agamishaala offers us. Regardless of the intention with which we come into these spaces, the excitement and the warmth draws us all in, and the spirit that we bring with us is the magic that charges these spaces with a palpable potential.

The act of containing can also have a passive, almost negative connotation—associated with ideas of limiting, constraining. The contents may take the shape of the container and would be limited by it. But in the case of the Shaala, the container must take the shape of the contents. Knowing how we, as the contained, come with such a range of intentions and expectations—each of us at a different point in our journey, each working at a different pace, and inhabiting different headspaces—building a container for a group as diverse as this is bound to be challenging.

Artika: “Since we are working towards building an emergent form of leadership and learning, we can’t ever be sure that ‘this approach or this activity will work’. Make it a template and ‘हो गया’. These are people who are incredible problem solvers, entrepreneurs, people who are doing the work. There is no telling them ‘how to do problem solving better’. they are already champs at it. You are only holding space to see and sense differently.”

The need to ‘see and sense differently’ becomes ever more crucial in the face of conflict and dissonance. The Justicemaker’s Mela was taking place in Bhopal around the same time that the 40th anniversary of the Bhopal Gas tragedy was being observed in the city. One event bringing together innovators and actors within the field of justice, and another seething over the injustice meted out to the victims of the largest industrial disaster of the 20th century. A few organisations from Bhopal raised objections to the Mela, opposing it to the point of boycott. The conflict was deep seated, pertaining to funding bodies, associations and affiliations—fundamental questions that had to be addressed. The questions loomed large in all our minds. But how is one supposed to seek mediation when the source of the conflict comes from unarguable pain, tremendous suffering, trauma carried by generations, and a disillusionment that has seeped into one's marrow? For the first time in several years, i found myself thinking—Which side are we on?

The container had to accommodate for this dissonance too.

Manish : “There is a longing to engage with those who are wounded. In that moment, there is a voice that tells me — there is no going back, you have to develop the capacity to listen. You need to let go of the excitement of innovation, change, transformation—and whatever those words mean—to be with the unresolved pain.”

“Challenges change changemakers—We are here for resolution but can you sit with something that hasn’t changed?”

As Artika mentioned during our conversation - “the lenses that we bring can limit us to thinking what the entirety might be”. Our sensing journey had to begin with a shift in perspective.

Swapnil and Abhay, fellow Shaala members and the co-founders of Zenith, were invited to set the context for us, both of them having worked in Madhya Pradesh for several years and bearing a knowledge of the movements, histories and undercurrents that inform the present landscape of this region. They told us about the various people that make up the state and the hidden threads that connects everyone to form a larger identity of Madhya Pradesh; that some of the strongest movements in the state were around the forests, due to the influence of the region’s Adivasi culture; about the divisions within the people’s movements in Bhopal, rifts caused by differences in ideologies and clashes over resources; and how the new generation is just not able to see themselves fit into these movements, as they have not been able to make the vision that they spoke of any more ‘real’ than when they began…

A question emerged that seemed to resonate with everyone.

‘इस नए युग का आंदोलन कैसा होगा?’*

Manish : “That question—Abhay was the first glimpse of that light. The question didn’t land immediately, it was developed in Muskaan. मेले में clearly दिखा , movement को पहले समझना होगा. नए युग के movement में जाने से पहले, इस movement को समझना होगा.”

That is the clarity, the light that comes through the crack. Manish referred to the song by Leonard Cohen, where he sings “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in”.

Artika : “We are operating in a world that has shifted and changed in so many ways. The question to ask is not ‘how to disrupt what has gone on or question it’, but rather ‘how can we honor what came before us and yet grow into a new paradigm’.”

*What will a movement for this new era be like?

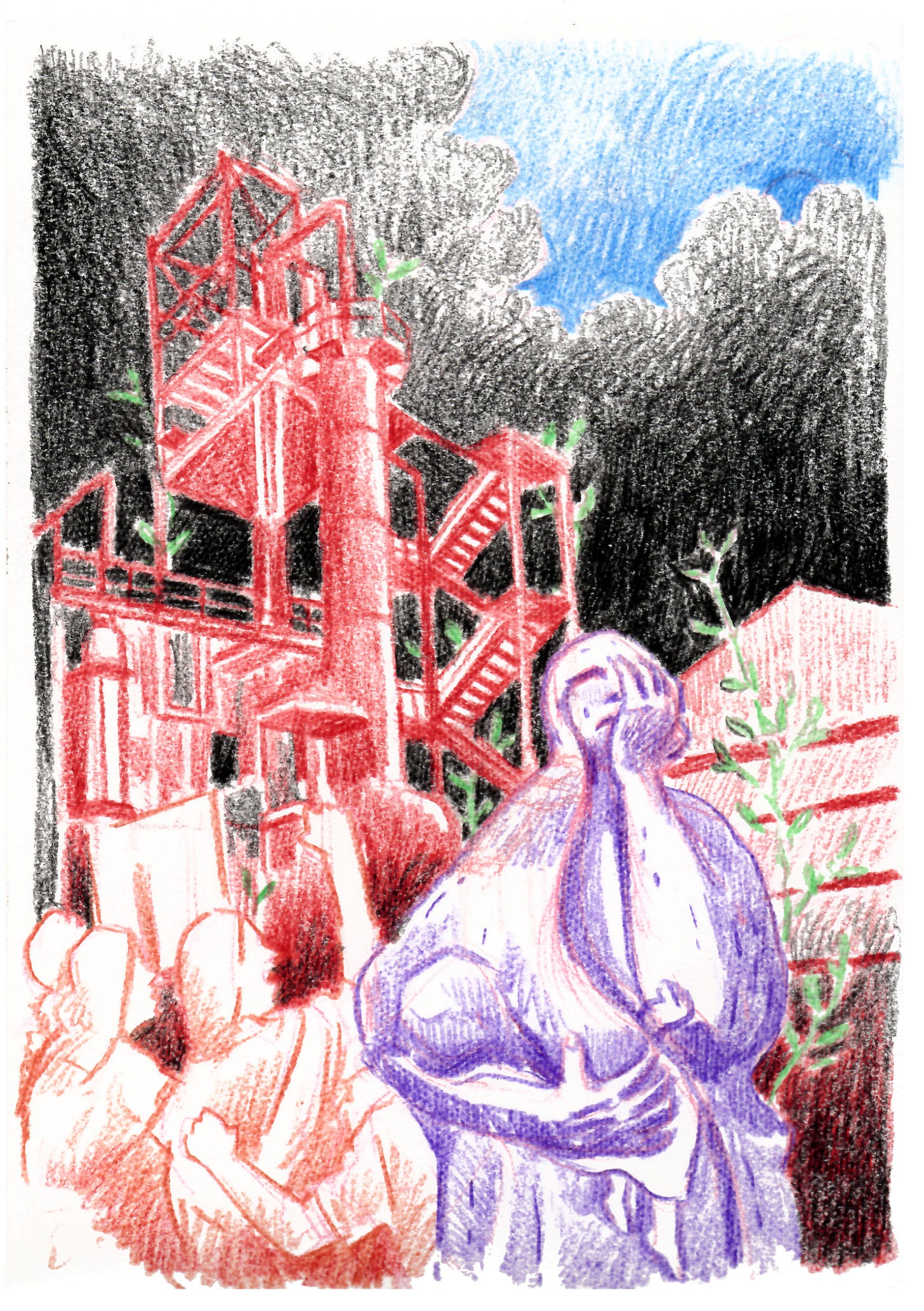

The sensing journeys at Shaala are those which require an intrinsic, bodily understanding. This took us from the practice space on the terrace of the Jehan Numa Palace to the mitti ka ghar within the premises of Muskaan—an organisation in Bhopal that has been working towards the empowerment of children and young people from denotified tribes through education and community development. The floors changed from polished marble to rough hewn stone; the walls, from pristine white to a patchwork of muddy browns. This transition between two spaces that are diametrically opposite to one another in structure, character and symbolism neither felt jarring, nor uncomfortable. It is quite possible that the diversity of realities that our group contains within itself, the various spaces of work that each member is acquainted with, prevents the group from feeling alien to either end of this spectrum. There are members acquainted with the tiled floors of corporate offices, the clicking of shoes that echo through dimly lit corridors of government institutions, the squeaky swivel chairs and the office desks stacked high with papers; while others are acquainted with the clamour of panchayat meetings and community gatherings, the cool dung plastered floors of village homes, the respite of woven charpoys under the shade of trees. All of us, inhabitants of starkly different worlds… and yet, here we all are together!

Muskaan welcomed us with open arms. Walking through the premises of the Jeevan Shiksha Pehal, the school that is housed within the mitti ka ghar, we could hear the muffled sound of activity coming from the classrooms on the floor above us, glimpses of children peeking out of windows. They breezed in and out of the classrooms, with not a hint of the disciplinarian temperament that is so intertwined with the notion of educational establishments. The children, the teachers, the resident dogs and the birds, were all allowed to move and settle by virtue of their own free will. And yet, the classrooms were full, the teachers attending to an eager, attentive audience, the atmosphere charged with purpose.

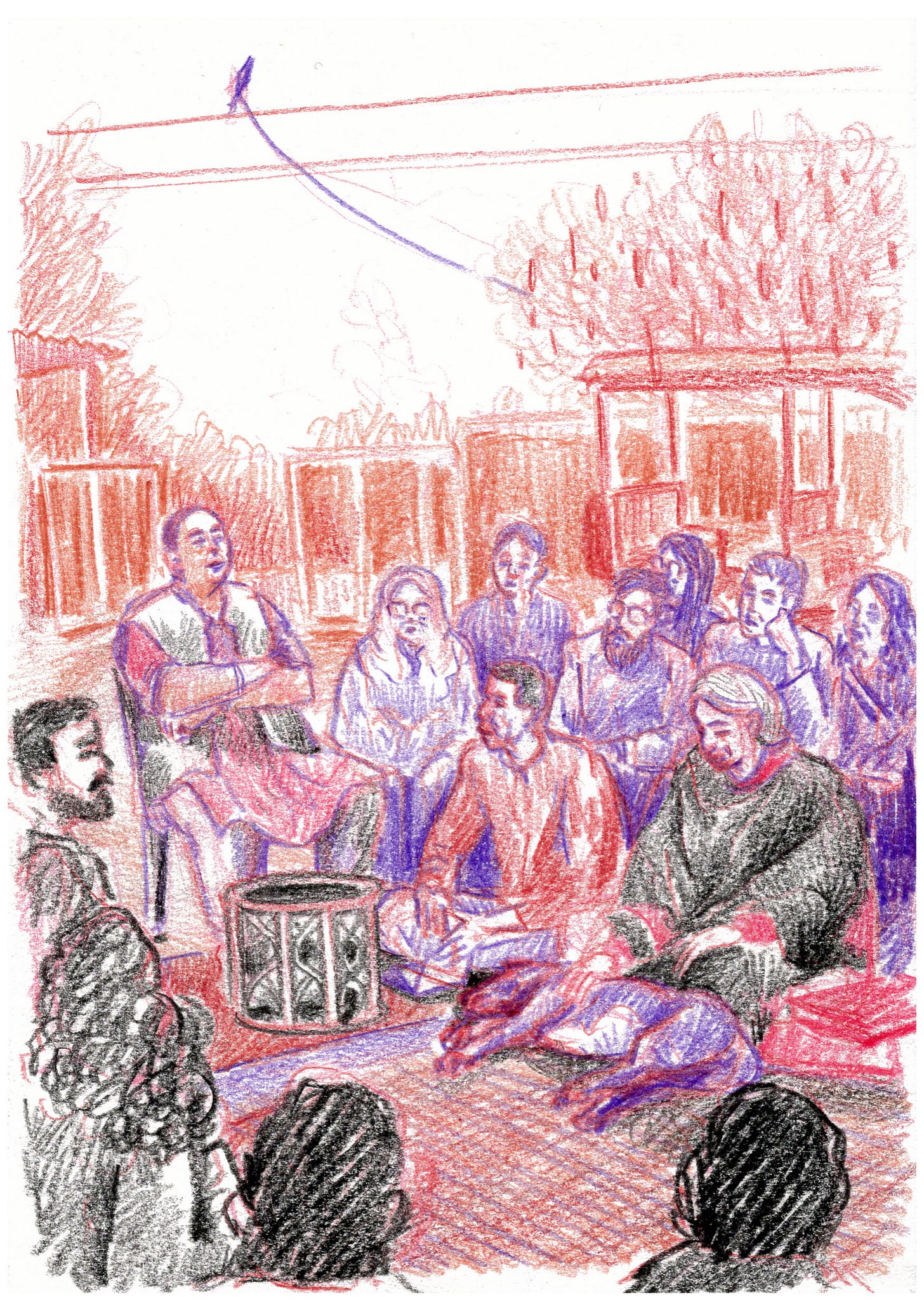

We gathered in the aangan, and formed a circle in the cool shade of the mitti ka ghar. Shivani, the founder of Muskaan, along with Roli, the founder of Youngshaala, were a part of our circle. They spoke to us about the nature of their work, the realities they have to confront, the way the movement is shaped around the needs of the children and youth they work with. As they spoke, we received their experiences in tender, attentive silence.

In the distance a lone kite jittered in the wind against a clear sky. There was a quality of stillness to the gathering, or as Manish puts it, ‘ठहराव’. The conversation trickled, bubbling out gently, unhurried. We spoke about hope, about exhaustion. The difficulties of working within marginalised spaces, the contradictions that come up within these societies owing to socio-political tensions, the impact these factors have on children.

My attention drifted, from the conversation, to the surroundings, and back again to the conversation.

The mitti ka ghar—with different shades of brown visible in segments all along its exterior— exuded such a powerful character. The elegant arched windows and doorways, the bare beams of wood that showed themselves unabashedly, the stylised motifs of the triangle and the square, all came together in a cohesive uniformity. I noticed the lack of crisp, sharp edges, the precise corners, the unbreaking straight lines— hallmarks of modern construction. I myself find a lot more comfort in slightly wavy, imperfect lines that are achieved when one draws free-hand, rather than the clinical, characterless lines one achieves with the use of a ruler. They just feel more… humane. The entire mitti ka ghar was filled with these beautiful, imperfect lines.

There was one child who decided to attend our gathering in the aangan. Like a little butterfly, she made her way from person to person, settling down in one lap, and then fluttering over to another. The people within our circle extended their arms and smiled as she passed, and she in turn settled with them for brief spells of time. She responded only to affection, the image of innocence, and she returned the affection almost as though she knew no other language—clinging on to Mohit’s arm, wrapping herself around Sachi, perching on Himanshu’s lap—happy to be held and included.

“How do you look after yourself?”

“There is more hope with reversing the thoughts for children than it is for adults.”

“Since things are improving, the best i can do is wake up and continue working

for the 2 billion people whose lives haven’t improved.”

“I sometimes think that I don’t belong in this space.”

“We take pride in feeling superior to someone else.”

“What is the hope you hold on to, when it is so fast to corrupt?”

There was an honesty that the space brought out in us. The questions each of us asked were being dredged out from the deepest reserves of our concerns and preoccupations.

Manish : “It was confronting in its honesty, it confronted us with our own reality. The intention with the sensing journey is that it becomes a mirror that allows us to see an aspect of ourselves. And what did they show us—Shivani ji, Roli ji, and the children? The deep trauma that our society is living within. And that we are coping with it!”

“There was a helplessness within our group, confronting the moment ‘की ये इतना effort जो हम लोग कर रहे हैं, वो कहाँ जा रहा है?’.”

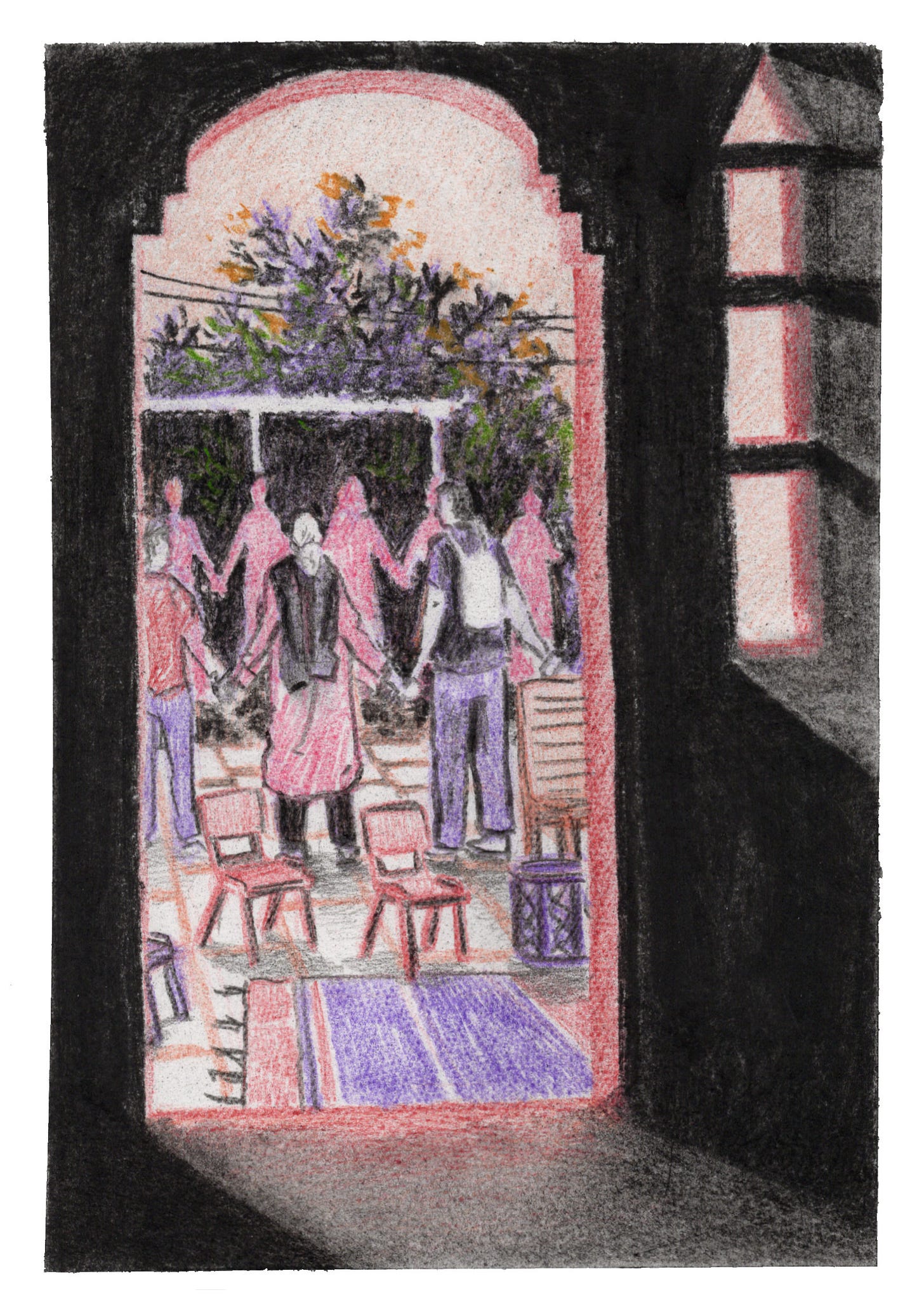

Movements cannot thrive in isolation. The struggle for humanisation, liberation and emancipation is a shared one, where there is a need for solidarity and kindness. Our objectives may be different, but that cannot separate us. The kindness that we were shown by Muskaan moulded the original dissonance into a resonance that we carried forward. The walls that were so filled with love and purpose, assuaged the immutable divide that the group had sensed.

After all, we are on the same side.

From where i was seated close to the stairs, i noticed that our discussion was being drowned out by the happy chatter of students that floated down from the corridors and the classrooms. Maybe that signified our position in that space—we were being gracefully accommodated, but we were not their priority. We too were interruptions at best, in a movement that was already taking place.

To conclude our sensing journey, Manish invited us to participate in a village activity*. I sensed a reluctance in my own body, a restlessness that kept me at the borders. In that moment, surprisingly, everyone felt like strangers. The village activity always has a measured rhythm, a dance that takes place in silence. Bodies at rest—lying down, eyes closed, leaning, sitting; Bodies in motion—walking, rolling, pacing. The light evening breeze rippled through the blossoming clusters of our village. I turned my back to the group, and looked out over the trees. Birds whizzed past noisily, parakeets screeching, swifts and bee-eaters chirping and clicking.

When the question of doing another activity came up, there were a few who said they don’t feel up to it.

Artika : “There are always hits and misses. Anxiety can come from someone saying ‘boss, nothing landed with me. I don’t know what happened’. And you sit with that anxiety. People ask ‘इसका outcome क्या हुआ ?’. It’s so hard to explain with something that is so visceral! But there is an innate sense of the outcome. It shows itself when you are at an Agami Summit, when you are at the Mela. To be able to stand your ground and say,‘It is happening, it will happen, and it is visible in many ways’.”

* The village activity is also a Social Presencing Theatre practice, derived from the Presencing Institute (MIT, USA).

Manish : “There is a clarity I am having now, which is that Agamishaala United is way bigger than what we are trying to do. In their first Shaala, people come in—like trees to forest—in search of their light and their insights and they engage with these practices that are non-verbal, creative, well designed; allowing them to go deeper into the mess to find their light in their own way. They take the inner journey and find a community to take the journey with.”

“Then there is a separate journey, which is that of ecosystem activation. These leaders also long for a journey—‘now that I am finding my own source, my own community, how do I create a movement?’. Shaala is individual focused and United is community focused, लेकिन ecosystem उन दोनों के बीच में है, that is where the movement building happens. That is the work that we still need to do.”

Artika : “Doubt can look like sitting with the ‘not knowing’. Every time we do it, it is a new experience for all 3 of us, and it comes with its own anxieties and discomforts. The practice is to sit with these feelings and say ‘oh, this is what we are sensing’, and we move forward . Our service to this incredible group of people is to be able to do this. Openness comes from the ‘not knowing’ and accepting it.”

The ebb and flow of the Shaala process, from doubt into clarity, and from clarity back into doubt, is the essential quality that allows this space to feel conducive for community building. As Artika later mentioned, clarity is not an absolute that defines the end point of our Shaala journey. Clarity, much like alignment, is an abstract that starts eroding just as you feel like you have it in your grasp. The Shaala journey is a constant process of coming together and sensing, and moving forward with hope and a collective assurance. We find strength in approaching doubt together.

“Clarity is found in how it pans out across those 2 days, in the dance with the field that enters the picture. You see this group of people who show up for their own journeys but also for the journey of the collective that comes after. You can see how they step in to help one another, how they discuss ideas with people, how they stand by one another. The field is growing in ways both felt and unfelt.”

I remember standing next to Shivani, as all of us formed a circle, holding hands, in a final gesture of gratitude before leaving Muskaan. She said - “ऐसा लग नहीं रहा की अपन सब पहली बार मिल रहे हैं. This group has such good energy.”

From my own experience, for someone to have felt this, they must have sensed a good listener in each of us. That mysterious 4th level of listening that i remember being introduced to in the Shaala at Ranikhet has become so accessible, and so necessary. Our group makes it feel almost natural, and maybe that is how it must be.

Manish : “Our work is to help cultivate the heart. कभी कभी ऐसा लगता है कि we will develop partnerships in another lifetime. इस lifetime में यही करेंगे.”

As we were wrapping up our conversation, i asked Aditi, Artika and Manish what they were earnestly hoping for, for each of us, in the coming year.

Aditi: “I hope we get to spend more time together, just to ‘be’. An agenda-less space is so precious, there are very few spaces where you can just be, and nothing is expected of you in that duration.”

“One of the nicest memories of my life is when Sid, Sachi, Rohit, Sam and I stayed together, cooked together. I want to have more of those core memories with these people. Just ‘be’ around them.”

Artika: “To be a little braver than we have been. Find more courage to step into the unknown.”

Manish: “These are the people i can grow old with, and i want them to be healthy. It gives me a sense of joy to travel with this group. I hope we take care of ourselves. There is so much the world asks of us, that we ask of ourselves. I hope we make spaces where we can lean on each other.”

I stayed back in Bhopal for a couple of days after the Justicemaker’s Mela. It was around this time that i got to spend an evening with Abhay. We hadn’t had the chance to get to know one another prior to this, having met rather briefly at the Shaala United in 2023. It was agreed quite mutually that it would be nice to talk and probably see the city together. We were both clear about wanting to find a place that was quiet, away from the traffic and the crowds, having had our fair share of interactions across the entire duration of the Shaala United and the Mela. We decided to go to the Upper Lake and hire a boat for an hour.

As the boat was pushed away from the dock, slicing through the water, the noise of bustle along the boat club promenade started to dim, and my senses adjusted to the sound of the water lapping rhythmically against the side of the boat, the squawks and screeches of river terns and gulls. Abhay and i sat in silence, we didn’t speak for the entire duration that we were in the boat. Occasionally, the guide would try starting a conversation, but we would return to a state of polite disengagement, each of us suspended in the buoyant solitude of the lake. Time seemed to dilate, the dimming daylight being the only sign of its passage. When an hour had passed we felt reluctant to go back to the shore.

The making of these core memories, the nurturing of friendships, is such a beautiful way to build an ecosystem. It certainly is a movement in the works, and i sense its relevance in moments like this.

Afterword

What roeqin captures through his words and art is something best felt. And yet, we are deeply grateful for the care, thought, and heart he has poured into giving form to the Agamishaala experience.

What began as his quest to understand the act of curating and convening has revealed something deeper - how a field is quietly, intentionally built. In Agami’s case, it is the field of law and justice.

Agamishaala beats like a quiet heart within the larger body of Agami. It draws strength from, and gives strength to, the wider ecosystem of actors and ideas reimagining justice in India.

Here, we hold the justicemaker at the center - not as an abstraction, but as a living, questioning, evolving human being. In exploring the inner biases and questions that shape their outer work, and in seeing what unfolds when these individuals become a collective - a sangha - the field reveals itself. And with it, the discomfiting questions it asks of each of us.

In a world increasingly marked by uncertainty, perhaps our truest work is not to cling to what we know, but to lean into what we don’t. Doubt, in this context, is not a flaw—it is a gift. It affords us openness, humility, and a readiness to imagine differently. Field-building, in our experience, demands this kind of unguarded curiosity.

Trust, too, is not built in a moment. It emerges through recurring shared experiences - through the quiet rhythm of being together again and again, asking deeper questions each time. It is not forged in one-off events, but in the continuity of relationships that remember and respond.

In roeqin’s reflections, we were reminded that Shaala is not a fixed form - it is shaped, moment to moment, by the people within it. Their honesty, dissonance, fatigue, and wonder. A single question - “इस नए युग का आंदोलन कैसा होगा?” - can shift the very texture of our gathering. And in that moment, we glimpse not just ourselves, but the evolving field of justice calling to us all.

A note of thanks to the friends and guides who keep us honest as we learn to do this better. You know who you are.

Gratefully,

~ Artika on behalf of team Agami

I love the artwork work. What medium do you use?