The Whale, the Code, and the Court | Note #15, Praani

Bioacoustics and machine learning are opening a new frontier in how evidence, harm, and more-than-human agency might be understood.

I have never gone deep-sea diving, and I have never met a sperm whale in the way that feels most honest, body to body, breath to breath, in the open sea. For now, my entry point is bioacoustics; the practice of learning through sound. A new year often brings new tools, new questions, and a slightly widened sense of what futures might be possible. For Praani, that widening has always been tethered to a simple commitment, we keep asking how coexistence can become a core concern for law and justice, in revealable, usable, institution-facing ways. This week, that question takes me to the mighty sperm whale, and to Project CETI, which is using machine learning and allied sciences to study sperm whale communication, with the hope that what they are saying may become intelligible in ways that can shift public imagination, and eventually, legal imagination as well.

When Our Measures of Intelligence Feel Too Small

We have long prided ourselves on our rationality and our large brains, and we often build our moral hierarchies from that pride, sometimes without noticing it. Sperm whales unsettle this confidence through the sheer scale and specificity of their lives. They carry the largest brains known to have existed on Earth, and their bodies are built for a under water world of pressure, distance, and depth. With a physiology that includes a neocortex and spindle cells, and with far greater stores of haemoglobin and myoglobin than humans, they can move through the deep sea in ways that make our own limits feel sharply drawn. Which forms of intelligence do we recognise when they do not resemble our own?

What can our ears hear? What has our legal imagination been trained to ignore? what would it mean to understand what whales are saying?

Consider how sperm whales live with one another: tight, matrilineal societies with long social memory and cooperative care. Mothers give birth with other females close by, newborn calves are watched and guarded by babysitters, and nursing can continue for years. Young whales also go through something that sounds remarkably like babbling — a long apprenticeship in sound — before recognisable patterns take prominence. Communication, in other words, sits inside a social world, and it is learned through clan relationship, patience, and repetition.

If sperm whales learn their communication through social life, and if their sounds carry cultural and linguistic histories that do not translate neatly into human categories, then their “sounds” deserve to be treated as language in the fullest sense of the word. If you would like to begin from listening, here is a place to start with sperm whale language. Some of these sounds can feel like digital data transfer, as if the ocean is carrying packets of meaning. That impression can be misleading, and it can still be instructive: what can our ears hear? What has our legal imagination been trained to ignore?

Once we take that step of listening, a further question follows. How could systems of law and justice, which are built around human language and human legibility, begin to make room for these other forms of meaning-making?

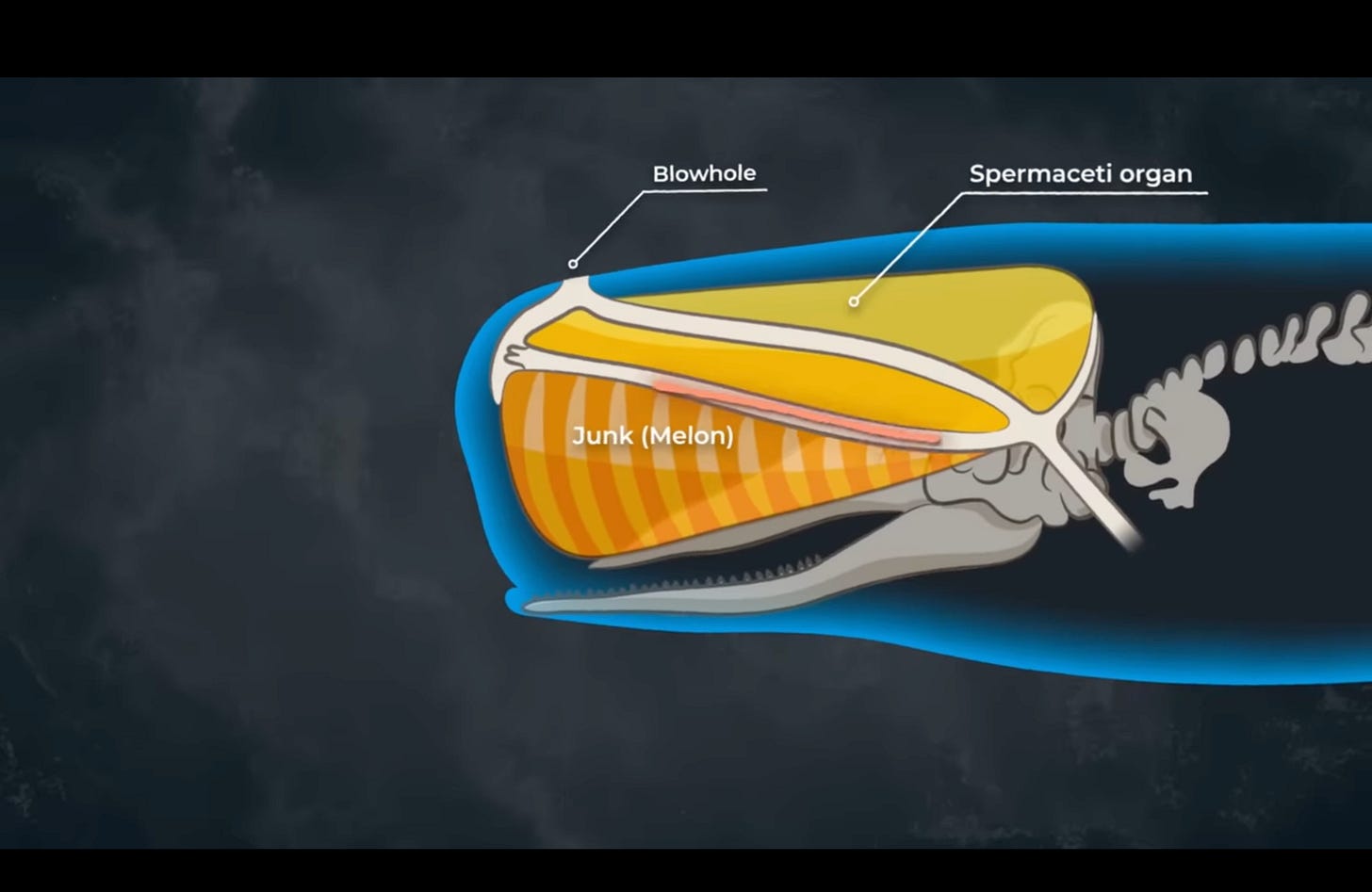

The sperm whale gets its name from the spermaceti organ, a large oil-filled structure in its head which create buoyancy by changing its volume and density, and enable sperm whales to dive to extreme depths. Early whalers mistook the waxy substance they found there for semen, and the misreading stayed in the animal’s common name. Today we understand spermaceti as part of the whale’s remarkable sound-making and sensing anatomy.

Project CETI, and a Question Big Enough to Hold Many Disciplines

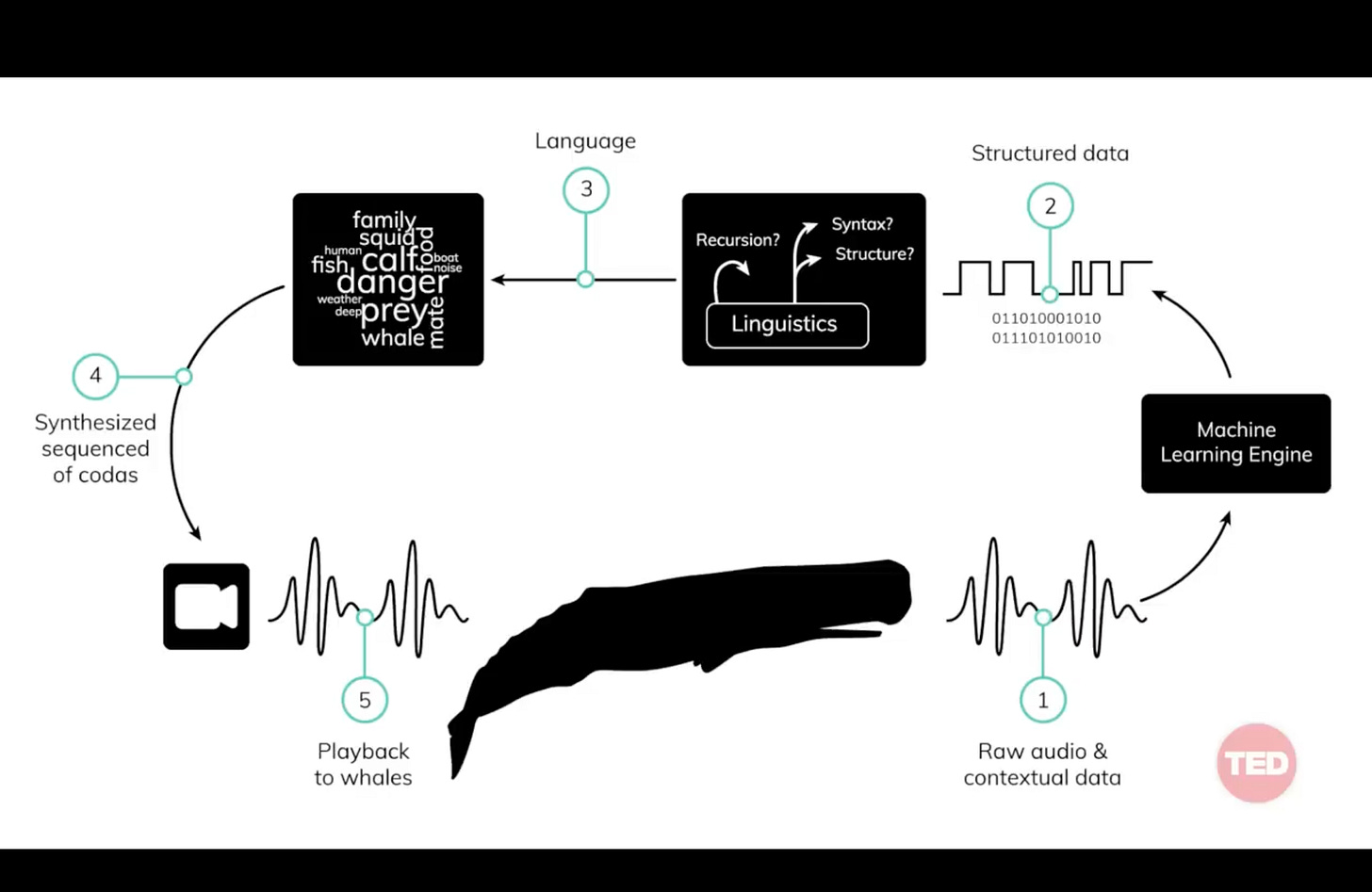

Project CETI is one of the most compelling efforts in this space. It brings together machine learning, robotics, natural language processing, linguistics, cryptography, complexity science, and marine biology to listen to sperm whales near the island of Dominica, guided by a question that is as simple as it is expansive: what would it mean to understand what whales are saying? This framing avoids premature certainty, inviting many disciplines to work alongside one another treating listening as a scientific practice with public consequences.

This graphic is showing Project CETI’s basic workflow, from recording whale sounds to testing interpretations in the field. First, researchers collect raw sperm whale audio along with contextual notes such as who is nearby, what the group is doing, and where the whales are located. That audio is then processed by a machine learning system, which looks for repeatable patterns and converts the sound stream into more structured data that can be compared across many recordings. Next, linguistics tools are applied to that structured data to ask whether the patterns have features we associate with language, such as stable structure, recurring units, and combinations that carry context.

From there, the team generates a “synthesised” sequence of codas, which is an AI-produced arrangement based on the patterns it has learned. Finally, they play those sequences back to whales and observe how the whales respond, using that response to refine the models and the hypotheses. In simple terms, it is a loop that moves from recording, to pattern-finding, to interpretation, to careful testing, and then back to recording again.

There is a lesson here for India that goes beyond admiration for a well-organised international project. When the question is genuinely cross-cutting and when the inquiry needs to last, how could the work be held? India has engineers and social scientists, linguists and marine biologists, legal scholars and court practitioners. It also has retired judges with decades of experience, and the energy to mentor new forms of inquiry. It has law schools that are hungry for work that feels institution-facing, and research institutions that can anchor long horizons. What often remains missing is a shared container, guided by a legible question, held by a team of teams that treats collaboration as praxis, and shaped by an ethical commitment to openness.

Project CETI also shows the value of being place-based. It is anchored to the specific geography of Dominica, a specific set of whales, and a sustained practice of observation and recording. In India, similar inquiry could begin with one region and one species. The point is depth and continuity, and an orientation that understands listening as a public good. This is where Praani’s commitments feel aligned, because we have been trying to build muscles of inquiry through small, steady documentation, and we have been trying to build a community that can hold complex questions without rushing to easy conclusions.

Codas, Clans, and a Social World Underwater

To return to why this work matters for justice, it helps to be precise about what sperm whale communication looks like. Sperm whales communicate through click vocalisations, and some of these clicks are grouped into units called codas. Different groups of whales have their own repertoires of codas, and these repertoires appear to be culturally learned. This shifts the question away from whether they make sounds, toward how they learn, carry, and vary a shared system across relationships and time; This presses against a familiar assumption that non-human life enters our institutions only through human narration.

The range of whale sounds are broadly of four types. Sperm whales produce louder echolocation clicks that operate like sonar for long-range sensing. They produce close-range creaks, often reported when prey capture is imminent. There are also clang-like sounds associated with adult males. Finally, there are codas. Even this simple typology shows that the ocean is full of meaningful acoustic labour.

These two clips offer a glimpse of sperm whale vocal life, clicks used in social contexts and echoes used to sense the world

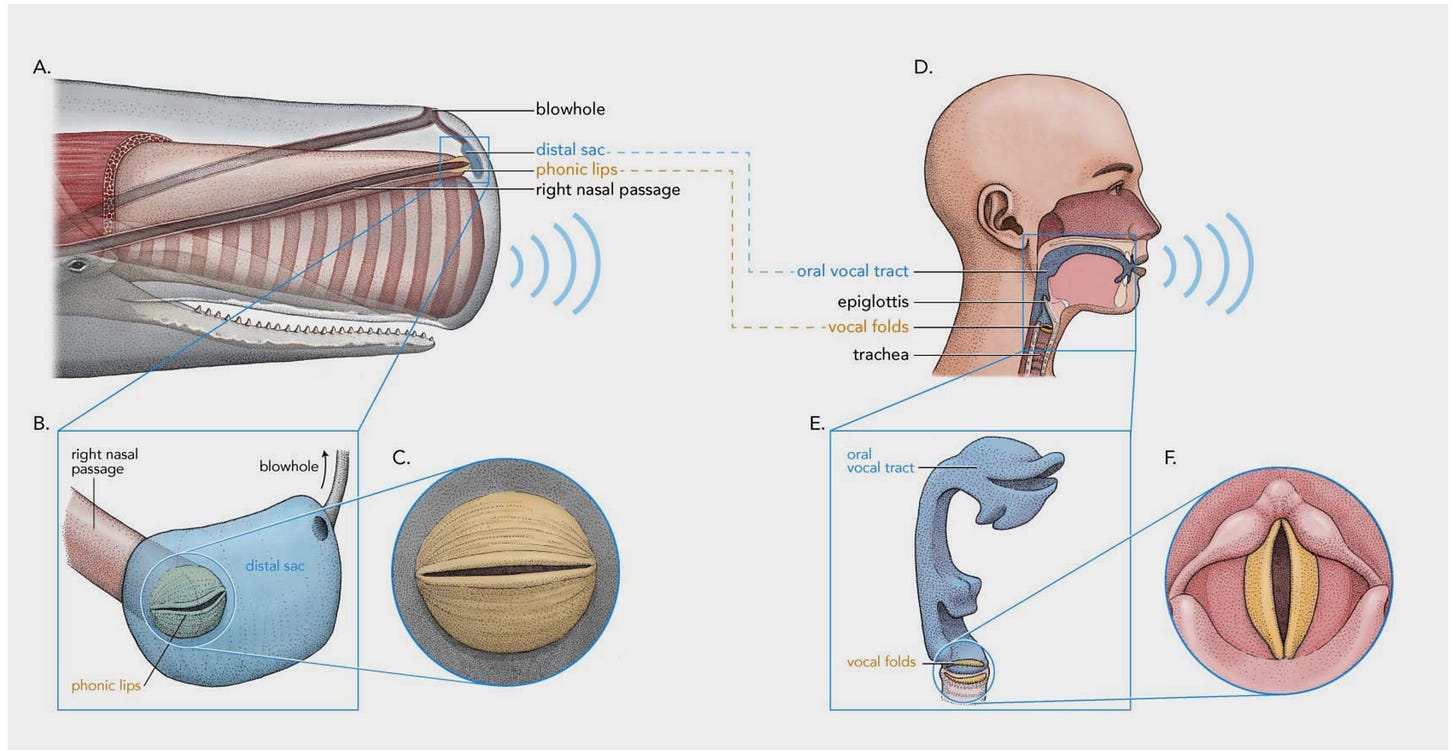

Recent work also suggests that these clicks may carry information through more than timing. Alongside the rhythm and spacing of clicks, there may be spectral properties, meaning the shape of sound across frequencies. In simple terms, it is the difference between counting beats, and also noticing timbre, texture, and the stable qualities that make one voice recognisable from another. One way this becomes more concrete is by asking whether some codas carry “vowel-like qualities”, shaped by resonances in the whale’s sound-producing anatomy.

When these spectral patterns fall into distinct clusters or types and show up in consistent ways, it becomes harder to treat them as random variation. Might whales be encoding identity, clan affiliation, or other social information in qualities of sound that human ears miss? If meaning lives in patterns that humans have not been trained to hear, then tools that help us listen well also reshape what we are able to see and notice as evidence in shared worlds.

This image makes a simple comparison between how humans produce vowels and how sperm whales might shape their codas. In humans, the vocal folds create the basic vibrating sound, and the vocal tract then shapes it into different vowel qualities through resonances called formants. In sperm whales, the phonic lips are thought to play the role of the sound source, producing the pulses we hear as clicks, and the distal air sac is hypothesised to act as a resonant chamber that shapes those clicks. The point of the comparison is to suggest that codas may vary through “vowel-like” sound shapes across frequencies, so studying whale communication can involve more than counting clicks and measuring their timing.

What Becomes Possible When Justice Begins to Hold More Than Words

Changes in science often travel into law with a time lag, yet when they arrive, they can be catalytic. The history of environmental regulation is full of such moments; with the discovery of endocrine disruption, the ability to measure particulate matter, the modelling of climate attribution, and the mapping of biodiversity loss. Bioacoustics has a similar potential.

The public circulation of whale sound has already changed sentiment in the past. The “song” of humpback whale, recorded and shared decades ago, helped many people sense whales as social and communicative beings, and that shift in perception mattered for politics and halt whaling. Listening can change what people believe is worthy of protection, and what they are willing to organise around.

At the Justicemakers Mela, and in Agami’s wider work, we have been experimenting with forms of inquiry that treat the world as a witness, even when the witness cannot speak in human language. When we hosted When the Earth Testifies, we were already circling a question that feels newly urgent. What kinds of testimony can institutions recognise, when the register is sound and when the witness is more-than-human? Bioacoustics offers pathways into this, but bioacoustics alone will not resolve the political struggles over land and life that shape harm in the first place. Its value is different. It can widen the evidentiary imagination for courts, and it can make certain harms harder to deny, expanding who gets to participate in meaning-making. Stay tuned for a follow up piece to this on using sound and bioacoustics as legal evidence in India.

At the Justicemakers Mela 2026, When the Earth Testifies gathered people who work closely with sound across ecology, conservation practice, and law, to explore how bioacoustics might help institutions understand environmental harm and respond with greater care.

Underneath all of this sits language itself. Human rationality often treats the absence of human-like speech as the absence of meaning. Sperm whale research presses against that habit, asking us to scrutinise intelligences that are mutually informative, human, more-than-human, and machine. It also invites humility, because even if translation becomes possible, it will come through conduits of models and probabilities. That makes the project ethically demanding in ways that are easy to overlook. That is where the real responsibility lies, in how carefully we treat these translations, and in whether we allow them to widen the circle of what institutions are willing to recognise as justice.

Sperm whales sometimes rest vertically, holding themselves almost motionless in the water column for short bouts of sleep. Because they breathe air, this upright posture keeps them close to the surface, so they can rise to breathe with minimal effort.

I will close with a smaller return to the whales themselves. They sleep vertically. Their sound can travel for miles, and their clicks can be forceful enough to unsettle a human body at close range. They hunt in depths that most humans will never witness, including that old, almost mythical encounter between sperm whales and giant squid. They remind us that the planet is already full of ways of being that sit outside our dictionary-defined categories. If 2026 is going to be a year of building emergent futures, then listening has to become part of our method. Listening for structure, listening for relationships, and listening for voices that governance systems have trained itself to treat as silence.

Stay tuned for part II of this piece which will lay out how sound and bioacoustics can be used as legal evidence in India.

Praani is our note on listening better to the voice of nature, ways of amplifying them, and finding pathways to bring them into our ways of governance. At Agami, we are deeply interested in how rivers, forests, animals, and even the winds and the stones, might speak into our deliberations on justice.