Listening Across Species: Designing the Multispecies Dispute Resolution Canvas

From the Belly of Fierce Creatures

Imagine a forest that is fecund, wild, and alive. Among its inhabitants are felines, invertebrates, primates, birds, frogs, and spiders, all living in cohabitation with mud, rivers, microbial life, and unending acres of tropical foliage. As an earthly neighbour, this forest is often visited by a moist and wispy cloud cover which unites the arboreal and non-arboreal life in the forest much like a shared, collective breath. Now how would it be if this ‘forest’ releases from its belly - a song? Would this song even be considered a ‘song’? Would it be anointed with copyright, protected with royalty, and prevented from dissemination except with the forest’s permission — the forest with its inhabitants living in fleshy entanglements? Or would it test both the limits and emancipatory potential of justice systems?

How must justice systems evolve to recognise that protection, rights, entitlements, identities, harm, and dispute are not simply for human life but for all life? These are just some questions in what is an experimental provocation in the form of a legal petition to recognise the copyright of the Los Cedros Forest in Ecuador in co-producing the ‘song of the cedars’.

On one hand we can quickly dismiss this as another attempt to incrementally push forward the wheels of justice. Perhaps it is powerful to legally acknowledge the intellectual property of the forest. But this still operates within an older paradigm - one in which justice systems are staunchly carved against the image of a human being. In such a system (mostly) ‘rights’ not only form the bedrock but also entrenches an exclusionary and disembodied recognition of justice systems - to center an individual, to the exclusion of all others. In this system rights - by definition - cannot be relational but always concomitant, never entangled but always dependent on creating a hierarchy of winners and losers. Take the forest. Assuming the petition is successful and the ‘forest’ has rights what would that translate into? If the petition is premised on a notion of fuzzy, undefined co-production how do dominant paradigms of justice begin recognising this messy right?

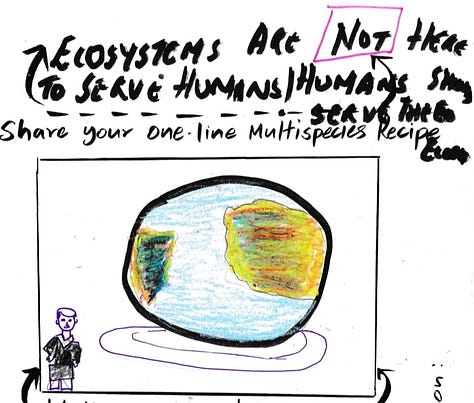

But what if we treat the petition not just as a plea, but as a provocation? Then its radical potential begins to emerge. It speaks law’s language mercenary-like, while simultaneously revealing its anomalies. Yet it deliberately bends the frame, introducing an ‘injured’ petitioner that is not human but an ecosystem. But much like in the fable where only a child could name the emperor’s nakedness while adults played along with illusion, this petition reveals the law’s self-deception — it uses the very tools of legality to expose how law fails to see what is plainly present: non-human presence, creativity, harm, and voice - the petition too has a similar effect. It takes law’s categories – like authorship, ownership, and harm and stretches them until they snap. By naming the forest as a co-creator, the petition quietly demands that law account for relational creativity and ecological co-production. It reveals how even progressive legal systems remain bound by narrow definitions of rights, subjectivity, and value. At its core, it reminds us: justice, as currently designed, largely serves human interest. The rest of life — and even what we call non-‘life’ — may squeak, roar, grieve, or sing, but still find themselves jostling for scraps in a system not designed for beings who exist in webs of mutual dependence, not for relationships that blur the lines between agency and environment.

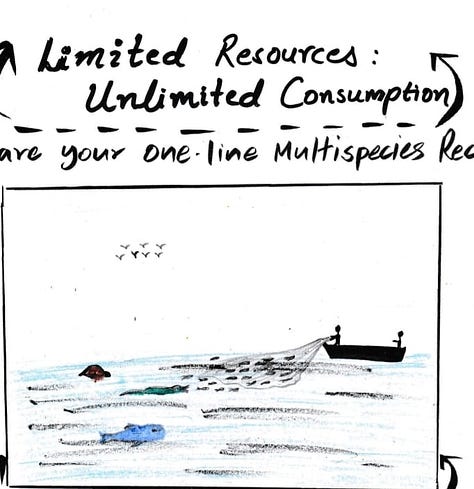

The ruptures that the ‘song of cedars’ gestures to are not unfamiliar in India. Our Wildlife Protection Act draws boundaries around forests, favouring the charismatic while displacing long-standing human and non-human relationships. Environmental laws permit ‘acceptable’ levels of pollution without asking what is acceptable to the river. Tort law reduces harm to compensation, rarely recognising injury beyond the human. Contract and commercial law repackage extraction as agreement. Even our dispute resolution systems presume that justice belongs to those who can speak, claim, and prove in human terms. These are frameworks shaped by a singular figure — the rational, rights-bearing human — often to the exclusion of all else. In order to muster a meaningful response to this prevailing system, a new artefact has been taking shape - The Multispecies Dispute Resolution Canvas.

The Travelling Canvas

The Canvas designed collectively by Agami and Socratus is aimed to be in part a systems-map which plots the dimensions - assumptions, flows and blockages - of our existing systems of dispute resolution in multispecies conflict. Across the Canvas, participants plot key dimensions of any dispute resolution system – the legal subject, the goals, the space of justice, the process, and so on. By making these dimensions explicit, the Canvas allows us to see the ingrained assumptions, leverage points and feedback loops, in the current paradigm, and to juxtapose them with alternative assumptions from a multi-species perspective. In another part, the Canvas is a provocation-in-motion - travelling from city to city, carrying malleable ideas for a new paradigm moulded and strengthened in halts. At each halt, the Canvas is moulded by voices across ecology, climate science, frontline justice work, artists, community organisers, conservationists and lawyers. It is these voices — unique in their lived experience of relating with multispecies life and conflict — that turn the Canvas into a living artefact, gathering stories, questions of exploration, and new relations towards multispecies justice.

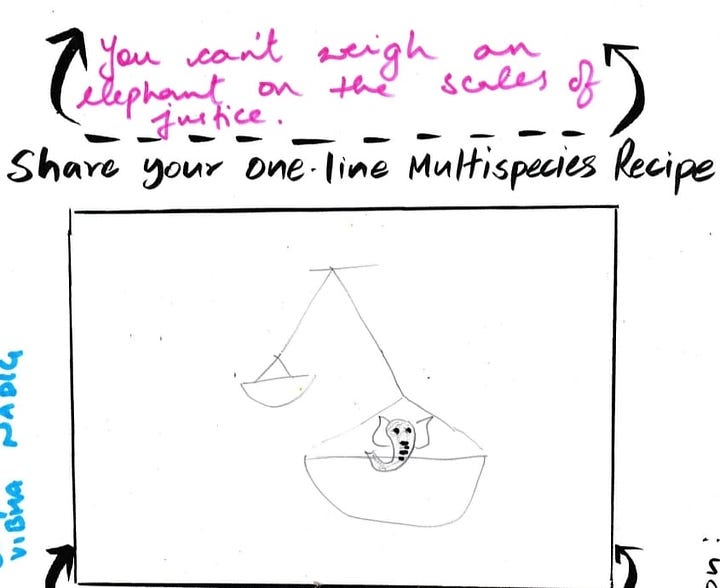

For example, In Bangalore, one thread that emerged through the Canvas was the failure of a one-size-fits-all approach to justice. The image of a giraffe, elephant, snake, and human all forced into a square space made this plain: our legal systems demand uniformity across beings whose lives could not be more different. This abstraction is taken further by another image, that of an elephant weighing down one side of the scales of justice, a quiet but forceful critique of how our current frameworks cannot hold the magnitude or difference of other-than-human lives.

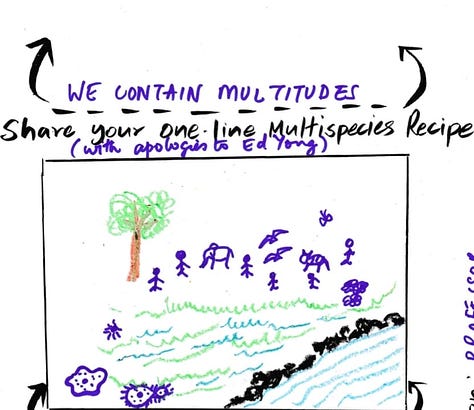

As a way forward, the Canvas turned toward humility: we must begin not by speaking for others, but by learning to listen to the smallest voices, like in the image of an amoeba whispering to a human ear. Justice, reimagined from the ground up, might start by designing from the perspective of those most easily ignored — the microscopic, the fragile, the unseen.

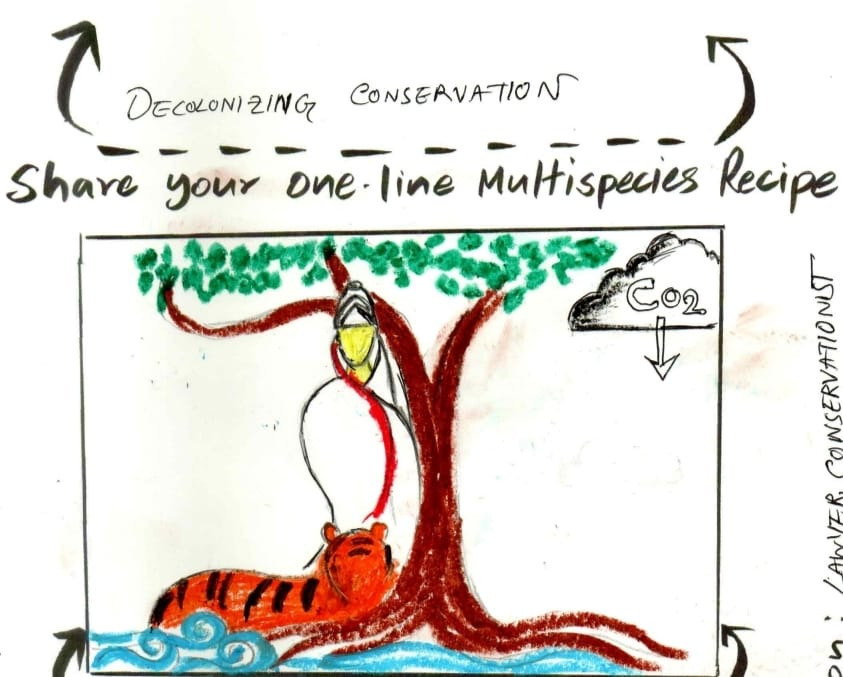

In Kolkata, co-curated with Sidharth Agarwal from Veditum India Foundation the Canvas brought forth traditions that already refuse the binaries of domination and protection. Through the image of Bonbibi in the Sundarbans, participants explored a longstanding relational treaty between forest-dwelling communities, tigers, and the spirit of the forest itself resembling a form of conservation not built on exclusion but on mutual recognition.

At the edges of the Canvas in Bangalore, quieter conversations over chai emerged too. A participant spoke of how fungi, often unseen, sustain entire ecosystems beneath our feet. Another reflected on how even our own bodies carry more microbial life than human cells and how we are, in a sense, already multispecies beings. These fragments reminded us that multispecies entanglements are not rare exceptions, but already very much in the fabric of our everyday lives.

Early Uncoverings, Learnings and Recipes of Change

Using speculative case studies of multispecies conflict and the multispecies recipes’ as a form of art to articulate new paradigms, the first two canvases started peeling off older layers.

Together we articulated that the goals of the prevailing system often boil down to maintaining order, protecting private rights, and facilitating commerce. Even “justice” tends to mean resolving disputes efficiently or assigning fault and compensation – rarely does it mean restoring harmony between species or healing ecological wounds. The space of justice is also constrained: a physical courtroom or tribunal where humans speak in specialised language. An elephant’s forest or a river’s estuary is not considered a legitimate venue for justice – those places may be the locus of conflict, but we uproot issues from their ecosystems and squeeze them into marble-floored courtrooms far away. The process we inherit is adversarial and formal. It pits parties against each other (usually two human sides arguing), follows rigid procedures of evidence and argument, and results in a win/lose judgment. Timeframes are short-term – lawsuits address past acts with little capacity to plan generations ahead.

From this, early values which could foreground a new system started emerging. The legal subject in this envisioned system is not just the individual human, it could be a river, turning ‘personhood’ into ‘riverhood’. This does not mean extending rights to the river, but designing a system which situates the river, or rather its right to flow and flourish, at the center. The goals shift from compensating for harm towards restoring fragile uncompensable ecosystems. The process becomes participatory and dialogic which not just include the judge and a lawyer - a bench and a bar - but multiple, intersecting disciples of ecology, environmental sciences and indigenous knowledge systems.

To be clear, these are exciting but early learnings. But within these speculative sketches there are brief glimpses of what multi-species justice might truly entail. A new vocabulary to speak, learn and do collectively.

Calling for Co-creation of the New

The canvas’s travels have only begun. In the next few months the canvas will halt at Bhopal, Bhubaneswar, Goa, Mumbai, Pune and Delhi. By no means are these the only destinations, and this is an open invitation to hop on and shape its direction. The Canvas at its core is a co-creation from conversations and collective action taken by innovators across disciplines. As we move forward, we invite even wider collaboration to shape, stretch and evolve this collective exploration of multispecies justice. Do you have a story of a community defending a river’s rights, or a court somewhere in the world that allowed an animal’s interest to be heard? Bring it to the Canvas. Do you see a blind spot in our approach? Add your perspective to fill it.

This project thrives on participation and diversity of thought. If you are an artist, draw for it. If you are a lawyer or judge, consider lending your pen in drafting a hypothetical judgment from a non-human perspective. If you are a student or activist, organize a local event to host the Canvas – even in a simplified form – in your community. Most importantly, offer your support and imagination. The Canvas is moving with the passion of those involved. We welcome co-creation in all forms including research, writing, facilitation, or simply spreading the word. Some early questions which we invite you to hold and explore with us are:

What could micro-architectures of justice - including sites and processes - look like if it were designed keeping in mind the right of a river to flow?

How might we rethink evidentiary paradigms and listen to harm and injury if it is expressed beyond human speech?

The next Canvas gatherings are being planned in Mumbai, Goa, Bhubaneswar, and Bhopal during the months of May and June. If you are interested in participating, hosting, or contributing in any way, please reach out to Atreyo and Smriti at atreyo@agami.in and smriti@socratus.org.

As Amitav Ghosh once noted in his reflections on climate and culture, our collective failure has been a failure of imagination. Here is a chance to flex our radical imagination in service of justice. It starts as a conversation – perhaps even a whimsical one – but that is how every transformation begins.