In Spotlight: Indus Action

Reworking India's welfare system to effectively serve citizens at critical life stages

“Our end game is to organise India’s five-hundred-plus fragmented schemes into a consolidated portfolio of four to five high-value entitlements that ensure delivery of ₹12000 per annum (₹1,000 per month) to every vulnerable and poor family in India.”

This is how Indus Action describes its 2030 mission.

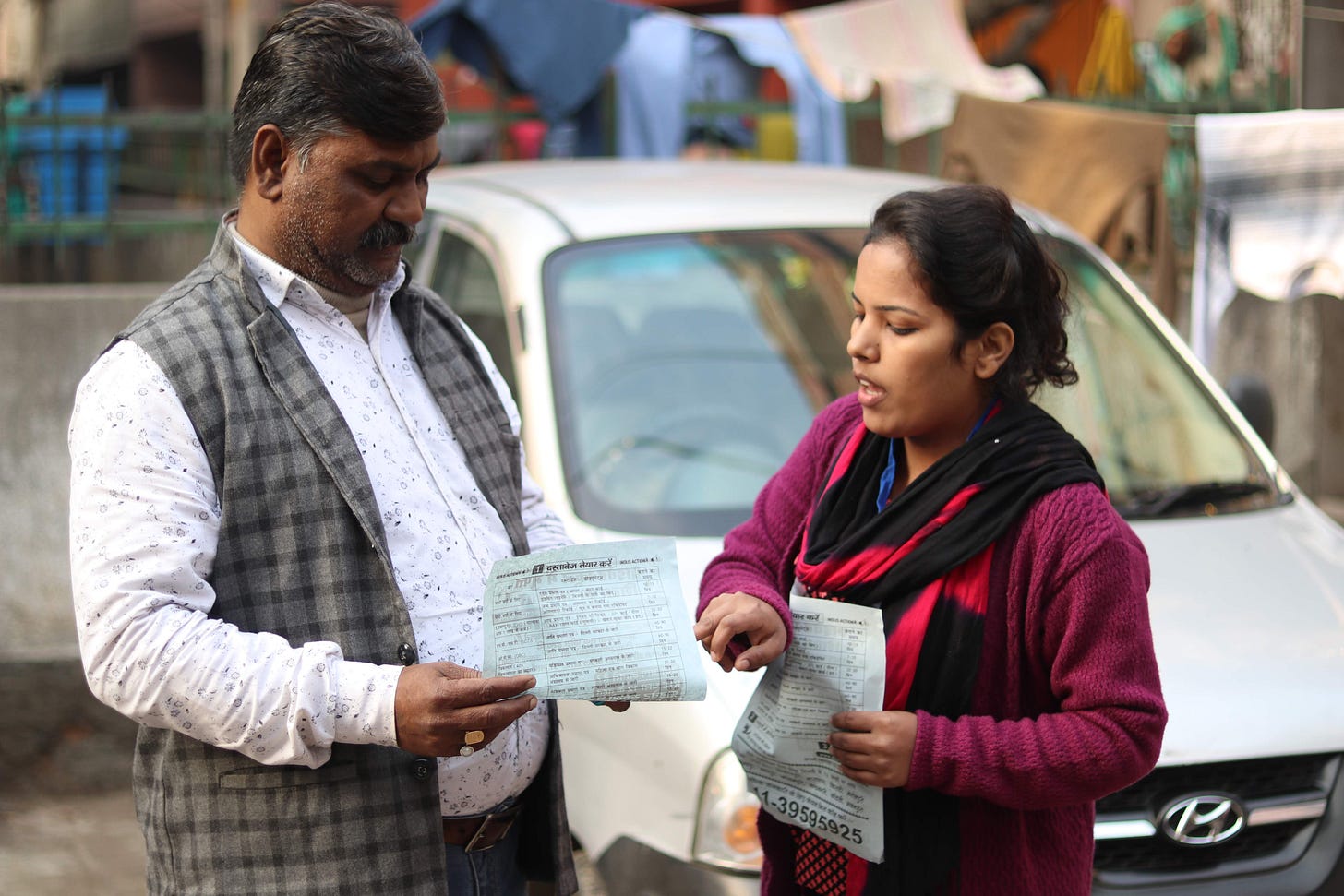

Today, a woman from a low-income family who’s expecting a child or has recently given birth is entitled to benefits under at least three distinct schemes: wage-loss compensation and maternal health (PMMVY), maternal nutrition (ICDS)birth in a hospital (Janani Suraksha Yojana). If she is a migrant or a construction worker, she will also be entitled to benefits under the Building and Other Construction Workers Act 1996. The fragmented design of the five hundred-plus schemes launched by distinct ministry departments requires her not only to know about all these rights but also to apply separately for each of them and prove her identity each time.

On top of this, every single application becomes a nightmare to go through and follow up with, with ten transactions on average, because of government inefficiencies in the scheme execution processes.

So why does India have so many schemes and transactions, counterintuitive as it feels?

The first reason is to reduce exclusion errors (accidentally leaving out eligible citizens). Secondly, in a country with such exorbitantly high levels of welfare needs, bureaucrats have resorted to being highly specific about what needs they are addressing so that they aren’t erroneously including people who don’t have social protection needs (inclusion errors). Trying to balance these two aims of minimising exclusion and inclusion errors, the State has just had to keep adding more schemes to cover more ground.

Ironically, this has resulted in the State’s mechanisms having spread so thin that they don’t have the capacity to effectively design and implement over five hundred schemes in a user-centric manner for crores of individuals.

Instead of focusing on building bridges to reduce friction and enable citizens to access all their rights, Indus Action paused and asked themselves, “What’s the end game here? Not ‘servicing as many schemes as possible’, but justice delivery. What is a better design for India’s welfare state? Rather than spreading itself thin across multiple schemes, wouldn’t it be better for governance to focus on a few strategic schemes and do them well?”

The leverage points for efficient welfare

It is rather convenient to say that focusing on a few is more likely to produce better results. But choosing those focus areas becomes critical to making this plan succeed and, specifically, asking what areas need conscious and concentrated focus to improve citizens’ welfare with a multiplier effect.

Here’s where Indus Action elegantly steps in.

“Based on criteria such as high social return on investment and vulnerable moments in a citizen’s life cycle (moments that matter), we have chosen to focus on the implementation of the Right to Education (Children), Right to Food Security (Mothers), Right to Pension (Elderly Grandparents), Right to Livelihood (Migrant Parents), and Right to Health (Family)”, they outline.

Building a stronger ecosystem for Rights and Entitlements:

Indus Action is not merely looking at servicing citizens with last-mile delivery. To work better, they have adopted three strategies to build the needed ecosystem for rights and entitlements (PoWER - Portfolio of Welfare Entitlements and Rights).

On building the capacity of the citizens

First, they build the capacity of the citizens to know their rights and share with the government exactly how their experiences in seeking these rights should be. Indus Action outlines a trajectory for citizens to be involved on all levels, from seeking information about rights to being community leaders spreading rights awareness to being co-advocates and co-designers in policy change. For instance, labourers that Indus Action initially engaged with on scholarship schemes for their children surfaced that schools claimed there was no such thing. Working together, they discovered that schools were facing issues with the government website when applying for these schemes and hence, weren’t processing them. The community leaders worked with Indus Action to resolve the case for the schools, and more than one and a half lakh scholarships and admissions thereafter began getting processed smoothly.

This process of the community raising awareness of needed change has manifested in research that helps the State’s welfare mechanism ground itself on citizen-centric design for implementing schemes.

On building the capacity of the State

Second, they build the capacity of the State to deliver on these citizen demands. The transition from a disorganised and clunky five-hundred-plus scheme design to a boiled-down-to-fundamentals, highly sophisticated and collaborative design isn’t easy. To aid this transition and make it sustainable, Indus Action works closely with state government offices to hone relevant skills like collaborative leadership and design thinking. This work moves the State closer to implementing the needs that emerge from the citizens and making processes more citizen-friendly. One of the ways they have optimised processes, for example, is by supporting the design of consolidating databases of citizen data, so each family unit needs only to be validated once instead of every time they apply for a benefit.

On consulting workflows with the State

“We start with our diagnosis being shared to the government and that’s where we have the action-consulting part. We consult and co-create the process workflows and the eventual solutions with the state and with the state officers - right from decision-makers to frontline.”*

On driving systemic shifts

Third, equipped with learnings from both of the above and with both citizen and state allies, they are driving systemic shifts in the design of policy through either legislative routes or judicial routes. For instance, mothers (community leaders) who discovered that second-child deliveries didn’t get the same maternity benefits as first-child deliveries demanded they should. They had their first big win in February 2022. The government redrafted the policy to include second children as long as they are female, and the mothers have buckled down to push the scheme further to include all genders in the near future.

Indus Action is currently working on three of the five focus areas - maternity rights, Right to Education (RTE), and migrant labour rights - methodically optimising their way through the five hundred.

Currently operating in twelve states with a forty-plus strong team and nearly a decade old, Indus Action maintains that this is a long-term game. Redesigning the very fundamentals of how welfare works in India is a status-quo-altering event and so needs to be a calibrated and collaborative effort.

Note:

*Tarun Cherukari, co-founder of Indus Action, in conversation with Maria Clara Pinheiro during Agami Prize 2022.

Edited by Keerthana Medarametla and Supriya Sankaran.