Praani ki Kahani

Praani is our note on listening better to the voice of nature, ways of amplifying them, and finding pathways to bring them into our ways of governance. At Agami, we are deeply interested in how rivers, forests, animals, and even the winds and the stones, might speak into ur deliberations on justice. This note had gone out on Nov 20, 2025.

Offering For the Week

The Question that Khejarli Poses

How many human lives is a tree worth?

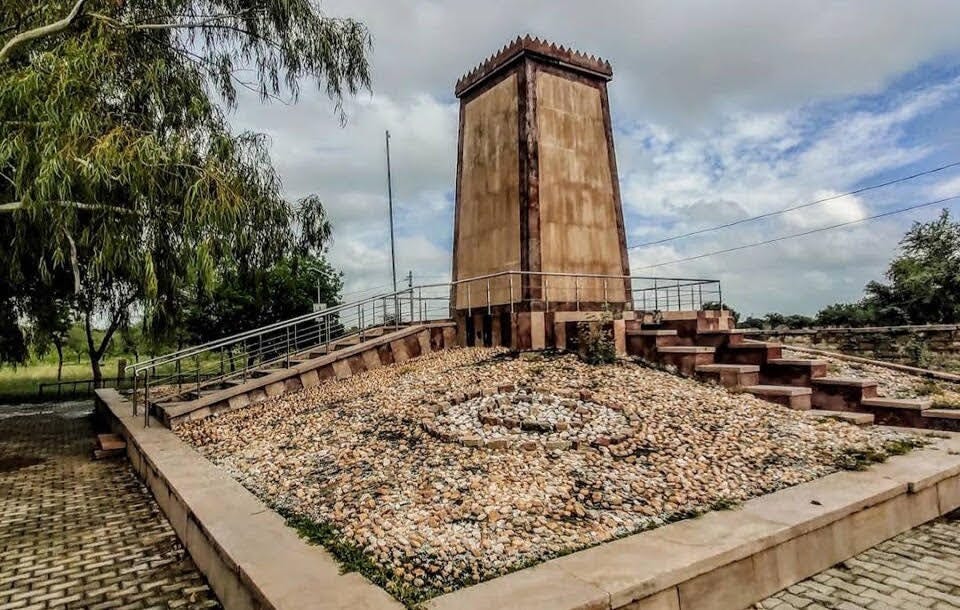

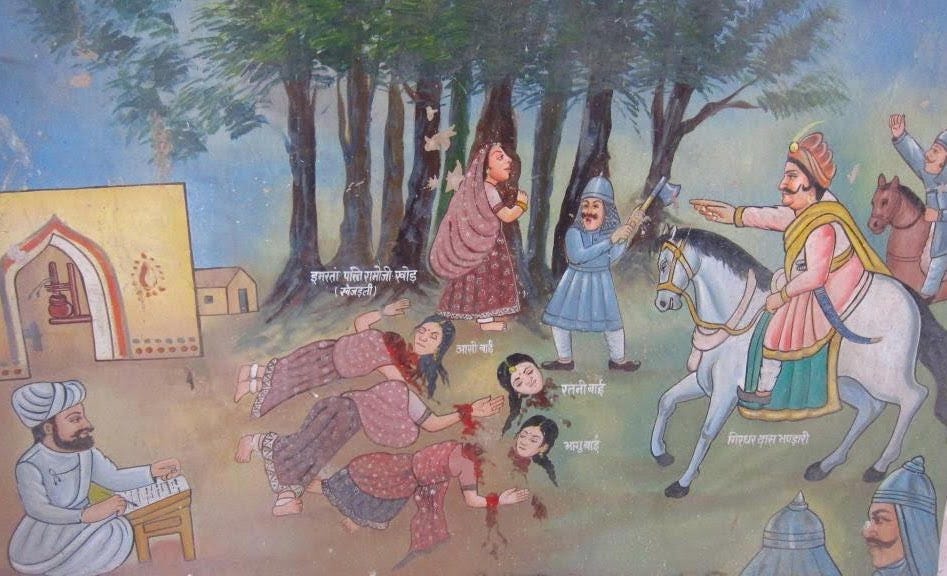

The question perhaps held a different answer in the Rajasthan of 1730 than it would hold in 2025. On 11 September 1730, in the village of Khejarli, something unfolded that in today’s vocabulary would be mistaken for barter or madness, though it was neither. When the Maharaja’s men arrived to cut khejri trees for palace timber, Amrita Devi stepped forward, held a tree to her body, and offered her head before she offered the tree’s. She was killed where she stood. Her three daughters, witnessing their mother’s severed head roll to the ground, followed immediately, each hugging a tree, each beheaded in turn. Each daughter tried to do better than the parent, each failed in preventing her own death, but each succeeded perhaps in the lessons that motherhood must have instilled in them, that life itself cannot be separated into human and nonhuman, that the tree and the self are one organism, and death to one is death to you.

As news travelled across Bishnoi villages, families gathered and decided that every tree felled would be met by one human body, placed deliberately and without panic between axe and bark. By evening, 363 people had been killed, each embracing a tree, each refusing to let the tree die alone.

It is tempting to read this as martyrdom or early conservation history, yet the event carries a deeper jurisprudence, one grounded in embodied equivalence where trees and humans inhabit a single moral field. The khejri tree itself carries this ethic. It survives on little water, stabilises soil, anchors fertility, and shelters life through drought. These gestures are often filed under ecosystem services, yet they feel closer to acts of creativity shaped from a desert that many consider unforgiving. The Bishnoi named the tree “Amrita Devi”, bringing human and vegetal lineages into the same breath. To harm the tree was to wound the self. The embrace they offered was a lived grammar of coexistence, held in bodies and carried through generations.

What Our Laws Choose to Protect?

Section 26(1)(f) of the Indian Forest Act, 1927:

“...Any person who in a reserved forest...fells, girdles, lops, taps or burns any tree or strips off the bark or leaves from, or otherwise damages, the same shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months, or with fine which may extend to five hundred rupees, or with both...”

...

“...Recently decriminalised (2024): “Acts such as felling a tree, felling or damaging a tree have been decriminalised from the provision of imprisonment for six months to only a fine that may range from 500 to extend to Rs. 5,000...”

...

Placed against the history of the Kherjali Sacrifice, the current language of law feels thin. Where the story of the Khejarli sacrifice shows us people who wanted to live with a sense of coexistence, the story that our systems of law and justice place at the center is one of property logic. Trees are protected only to the extent that they produce timber or constitute government property. They are never valuable because they are so tied to our heart, sinew, and soul. They are never protected because they are co-inhabitants in a shared world.

In many situations, trees are not even protected on an individual basis. They are only protected in mass form, as forests or as large aggregations of flora. The Forest Conservation Act of 1980 requires approval from the Central Government before forest land can be diverted for non-forest purposes, but this applies to land diversion, not individual tree felling. State level Tree Preservation Acts exist in Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and a handful of other states, but several states like Haryana have no tree preservation law at all. In this compensatory paradigm everything is interchangeable, and destruction becomes a transaction. It is the opposite of the Khejarli ethic where no tree was treated as substitutable and where the calculus was not compensation but safeguard. Safeguard with rootedness in particular soil, with relationships to particular birds and insects and humans who depend on them.

Returning to Coexistence and Utthān

The story of Khejarli asks us to examine what kind of justice becomes possible when coexistence enters the centre of our moral imagination. It is a reminder that the earliest forms of environmental reasoning in the subcontinent came from communities who saw land and life as deeply entangled, and who understood protection as relational rather than regulatory. If the Bishnoi sacrifice teaches us anything, it is that justice gains strength when it begins from attachment instead of abstraction.

To think about utthān, regeneration, through this lens is to see justice as a rising that is shared. A rising where trees are not processed as permits, where loss is not priced, and where protection does not wait for a category like “forest” to be triggered. It is a rising where the social body of law learns to hold the humility of the khejri, knowing that its own endurance depends on the endurance of the more-than-human lives around it. Coexistence must become a core concern for justice, its core structure. Everything else flows from there.