Praani ki Kahani

Praani is our note on listening better to the voice of nature, ways of amplifying them, and finding pathways to bring them into our ways of governance. At Agami, we are deeply interested in how rivers, forests, animals, and even the winds and the stones, might speak into our deliberations on justice.

Offering For the Week

Narrative, Context, and All Things Unwelcome

We reach for “narrative” and “context” all the time. In a quarrel, they are the missing pieces that make yesterday’s sharp word legible. In love, they are the backstory that softens a mistake. From the outside, we often shrug and say there must be another context at play, some narrative we do not see. Our systems of law and justice often lean the other way.

They prefer the crisp edges of expert testimony and easily verifiable fact, the language of positivist science. What does not fit that shape is filed as hearsay, collateral detail, or noise. A whole layer of lived knowledge becomes a derivative, subordinate, and therefore unwelcome reality. Today we borrow the leopard’s lens and read human–leopard relations as a careful sum of parts, setting down the heavy hole so the pathways inside conflict come into view.

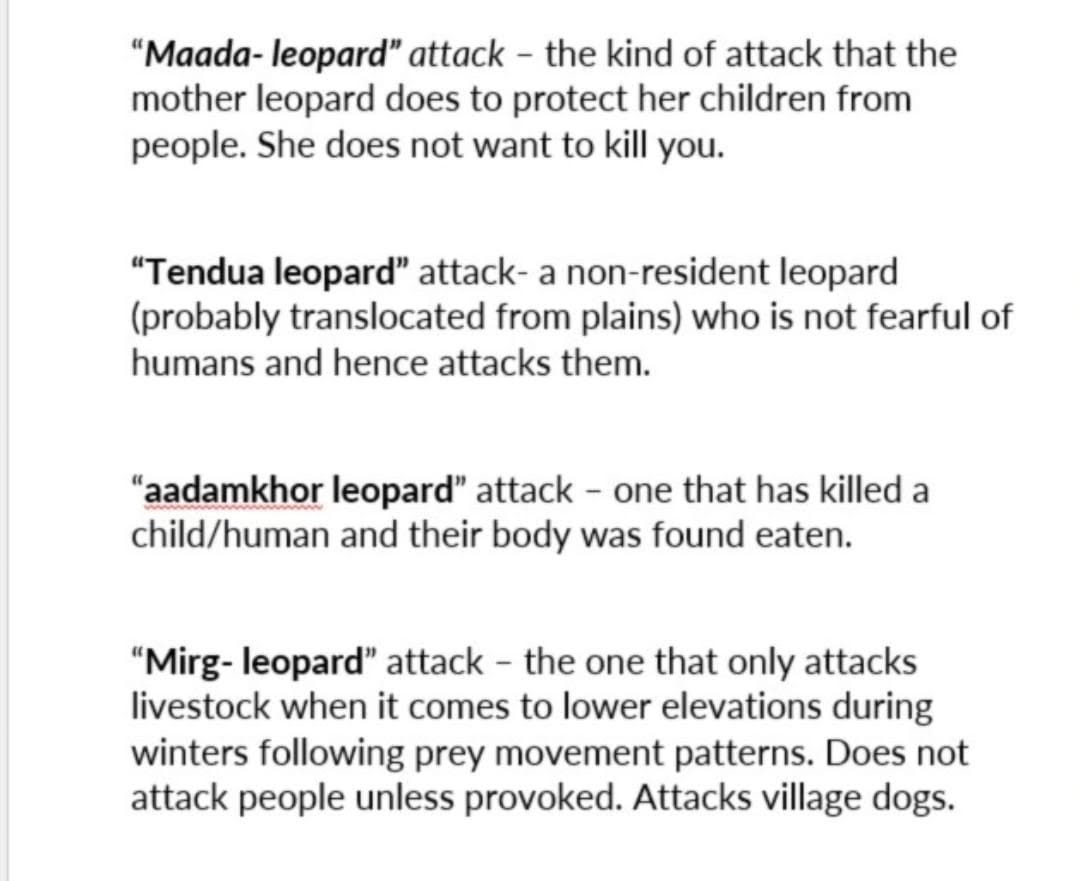

On the ground, people name and grade encounters with care. A maada-leopard is a mother defending her cubs. A tendua is a transient outsider, bolder and unsettled. An aadamkhor is the rare killer whose victim was found eaten. A mirg-leopard follows prey to lower slopes, takes livestock or village dogs, and keeps away from people. In their studies, Shweta Shivakumar and Dhee show how this vocabulary lays out a spectrum of intent and risk, moving from defence, through bold unfamiliarity, to predation on humans, and to predation on other animals.

The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and the files it generates usually read these events as a single thing, conflict, which then invites a standard response through “problem animal” permissions under Section 11. The spectrum vanishes in the record. When such oral taxonomies are held as evidence alongside formal reports, responses can be scaled to context, lethal permissions can be reserved for the truly dangerous, and cohabitation can be supported where behaviour points to avoidance. Far from softening rigour, reading narrative as knowledge recovers information people already use to stay alive.

The Non-Human Turn in Justice?

When we think of the words shy, elusive, and fearful, a leopard is not the first image that arrives. Yet in the villages that live with them, these are common descriptors. In their work, Shweta and Dhee record people speaking of leopards as shy, fearful, quick, elusive, and clever, with everyday observations about where they rest and when they move. They also note a change. What researchers call tolerant synanthropy, a habit of sharing space with workable accommodations, has in many places slid into reciprocal damages. One account describes a villager who, seeing a leopard drag away a goat at dawn, struck it with a stick; the leopard turned and attacked. The researchers also note that retaliatory killing appears in about a tenth of the stories they collected. This is how harm cycles in both directions, from livestock loss to human injury and back to a dead leopard. Holding that full chain in view helps explain why vocabulary drawn from lived settings matters, and it leads directly to the question of how justice reads such encounters.

Across many disciplines the non-human turn is already mapped. Law and its justice procedures are still catching up. A system built for human governance tends to see a leopard as a single entry under conflict, which leaves out the rules and patterns that guide non-aggressive encounters. The ethnographic record from Himachal shows people reading those rules closely and negotiating space through shared routines and signals. Bringing this turn into justice means reading ordinary, non-violent meetings as evidence. It opens different remedies in shared geographies, prevention that follows local timings and routes, and protocols that aim to keep coexistence intact rather than flatten it into a case file.

Notes from the Field

Much of the work on Praani began earlier this year, when we set out a Multispecies Justice Canvas to look for real pathways of how the voices of more-than-human life might be heard inside our systems of justice. Last week we wrapped our fourth canvas in Goa, after halts in Bengaluru, Kolkata, and Mumbai, and the artefact now carries drawings, methods, and small shifts in how we listen.

If you are new to the journey, start with the intent and scaffolding here: Listening Across Species: Designing the Multispecies Dispute Resolution Canvas. Then read Bharati’s reflection from Goa on how practice grows through place and relation, and how hope, like fungal threads, travels quietly through soil: Mycelium as method and justice as question.