A Bank of Possibilities

How river walking is unlocking Environmental Justice Innovation in India

The act of walking is as old as humanity. It is a physiological function that has carried us through history, geographies, from the realm of doing to that of being - and back. The cadence of putting one foot in front of the other - the rhythm of rest and motion - is inherently balanced. It allows the mind to meander through the landscape of lingering preoccupations, memory, the rare epiphany and is punctuated by the discoveries of the traversing body. One that is pressing against the earth - that is seeing, smelling, listening.

In Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit says of walking, that it is ideally “a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord.” This state, described as meditative and generative, is often where ideas are created, reconciled or discarded.

In a time when speed and efficiency preconditions any endeavour and as we try to dictate pace and exert maximum control over circumstance, walking upends these constructs and transmutes into a radical act. Siddharth Agarwal, the current convenor of the India Rivers Forum and the founder of Veditum India Foundation, has walked more than 4000km along the path of rivers. He reflects on how -

Information travels through ‘controlled highways on the internet’ and our physical bodies move mostly through ‘infrastructural highways’ negating all else that exists outside it.

Walking prompts a visceral engagement with realities that are not predetermined, it brings within one’s purview all that is ‘negated’ in the line above. These realities serve no purpose beyond brushing against our own - creating the friction that holds the seed of a spark. One could call it submitting to the offerings of chance, we think it is a ritual of opening oneself to receive.

One step at a time

As Siddharth sat in the middle of a vast farm tract during his long walk along the Ganga in 2016, he registered a journal entry that read:

Opportunities for work, stories and photographs are waiting everywhere, but these will not come to you on their own. You can either wait to stumble upon an accident that is to happen, or you can make these accidents happen; the choice is completely up to you.

Journeying on foot along rivers became a channel for these accidents, a membrane of exchange between him and the environment. It began as a resistance to the strong currents of the information highway. News and stories were being churned out for the mainstream, discounting the experiences of the marginalised and excluding vulnerable communities.

Walking became a way to slow down, know the ‘Everyday India’ and share stories from ground up. And as he walked along rivers - this temporal, temperamental and absolutely essential life force - the stories did begin to trickle in. Surfacing the many ways in which it co-exists with human societies - from its mythical heft to its contemporary disregard, from the wonders of the life it supports to its labile and destructive capacity. Its constantly shape-shifting form prompts layered and often contradictory relationships of reverence, dependence, fear, neglect and extraction.

Travelling over embankments and from one watershed to another, the complexity of these relationships with the river became increasingly evident. Observing large infrastructural projects - dams, barrages, hydel power plants, banks ravaged by sand mining, impending river linking projects - cemented for Siddharth the realisation that, how one choses to engage with the environment is determined by how they relate to it.

Walking is one way of building and nurturing this kinship. It facilitates an embodied knowing of the other - a connectedness not just with the destination but all that greets or ambushes one along the way, returning to Rebecca Solnit, “it is the means and the end”. The re-establishment with ground realities and kindling a deeper connection with people has been a tug many spiritual, social and political leaders have felt. And they have answered to it by walking. Whether solitary or communal, the more known walkers from our history - Gautam Buddha, Guru Nanak, Mahatma Gandhi, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Vinobha Bhave and Shekhar Pathak - have had the lasting effect of galvanizing thought, action and community.

Creating fertile ground

For people to cultivate a deeply felt kinship with the environment, walking along rivers was institutionalised at Veditum as the Moving Upstream Fellowship in 2019.

The accounts of the fellows who walked along the Sindh, Betwa and Luni over three cycles of the fellowship plot a rich ethnographic map of the rivers and the lives they touch. The complicated interconnectedness between issues of employment, caste hegemony, government apathy, denuding forest cover, an increasingly erratic river, health, deceptive promises of development - emerge as a larger pattern from observations across their walks.

Encounters with human and non-human life that are a part of the riparian ecosystem, are intertwined with personal negotiations, challenging assumptions and reinforcing the sentience of the river. These journeys on foot, undertaken in pairs or trios, are nuanced by design blurring the boundaries between the internal and external - the self and the environment.

Eight fellows walked along the river Luni in Rajasthan through the months of February and March 2024 in the latest edition of the fellowship (co-hosted with SPP, IIT Delhi and Out of Eden Walk). In the video below, they offer a glimpse of how their relationship with the river as an entity changed and the reflections it prompted.

Fellowships such as this come at a time when it’s vital to sense situations deeply and address problems differently. With established disciplines in any field, including the environment and its intersections with other spaces such as law and justice, there is a tendency to revert to known frameworks of thinking. Experts, valuable as they are, tend to crowd out new seeing and doing. Classic models of environmental advocacy are one example. The Fellowship enables a new generation of potential changemakers to sense ground realities and their relationship with them in altogether new and profound ways.

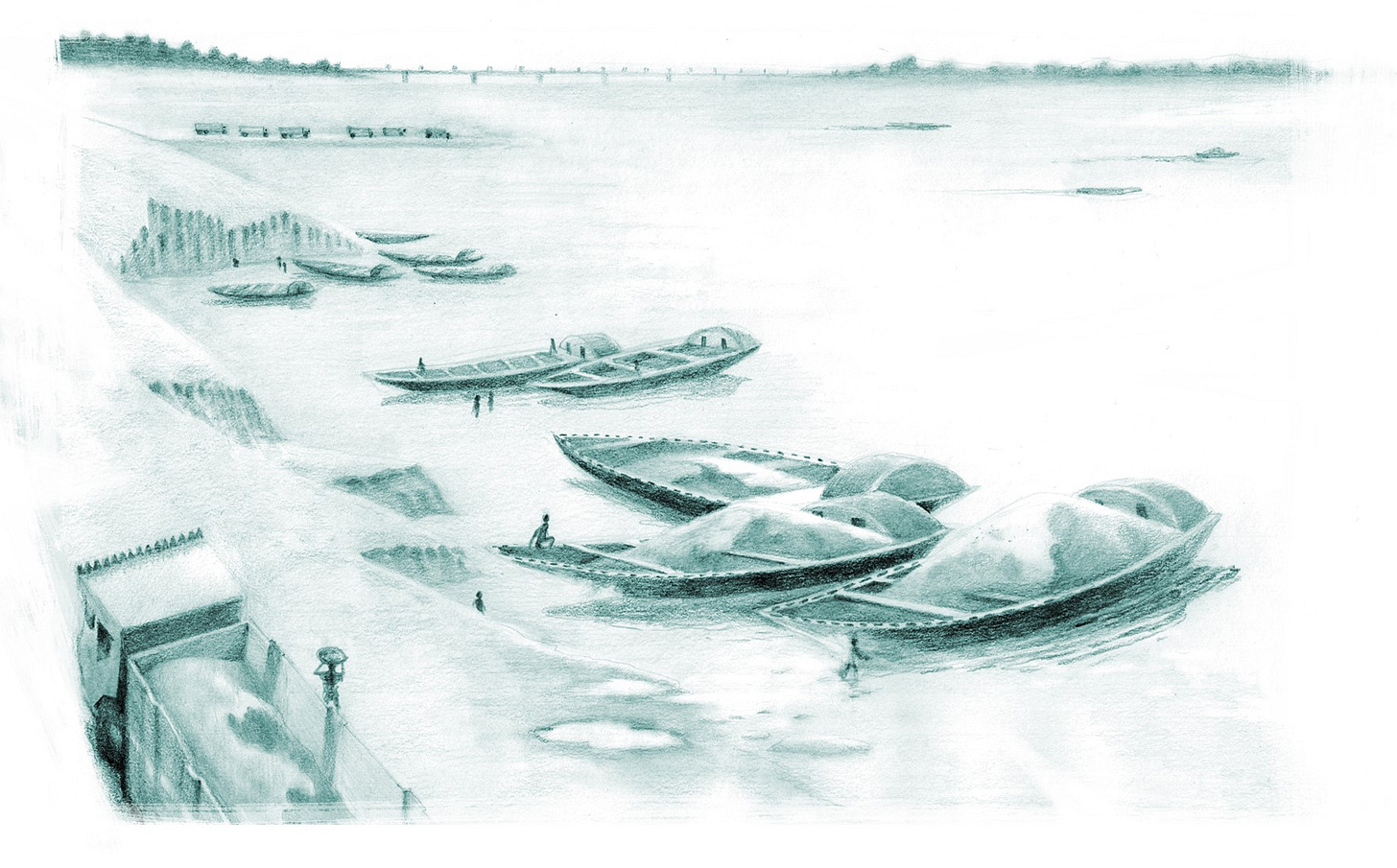

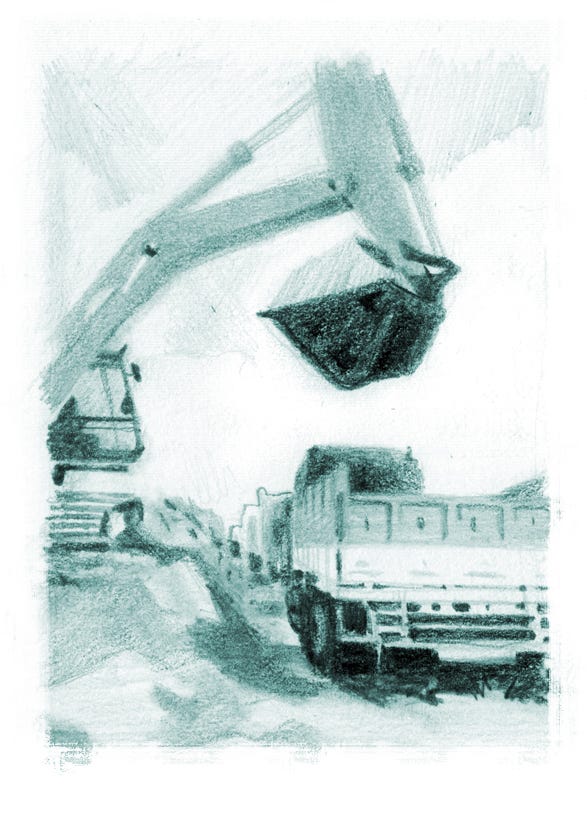

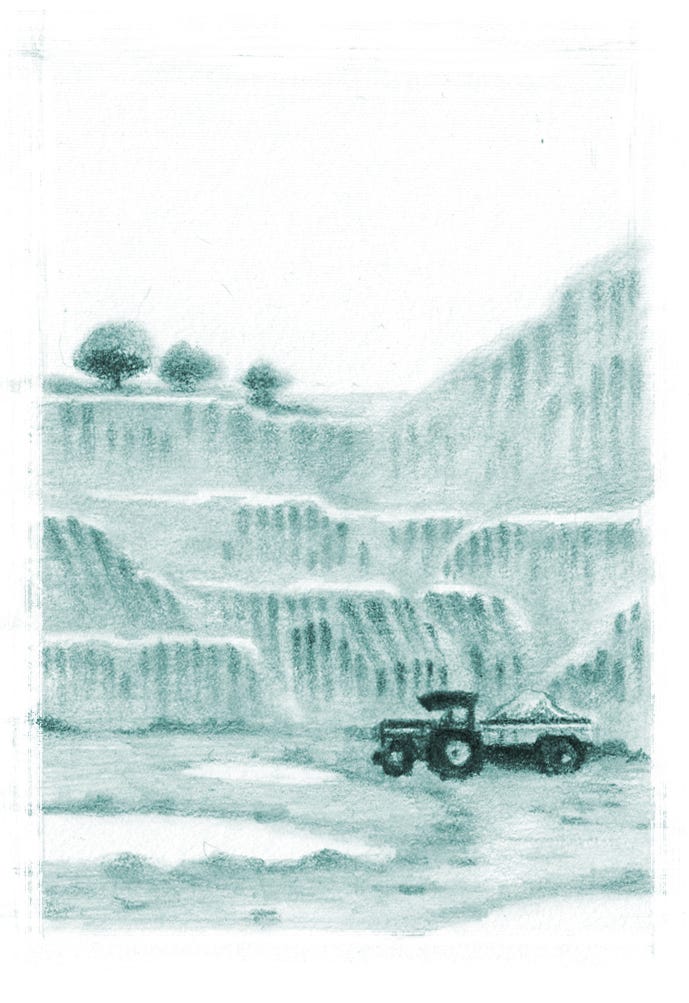

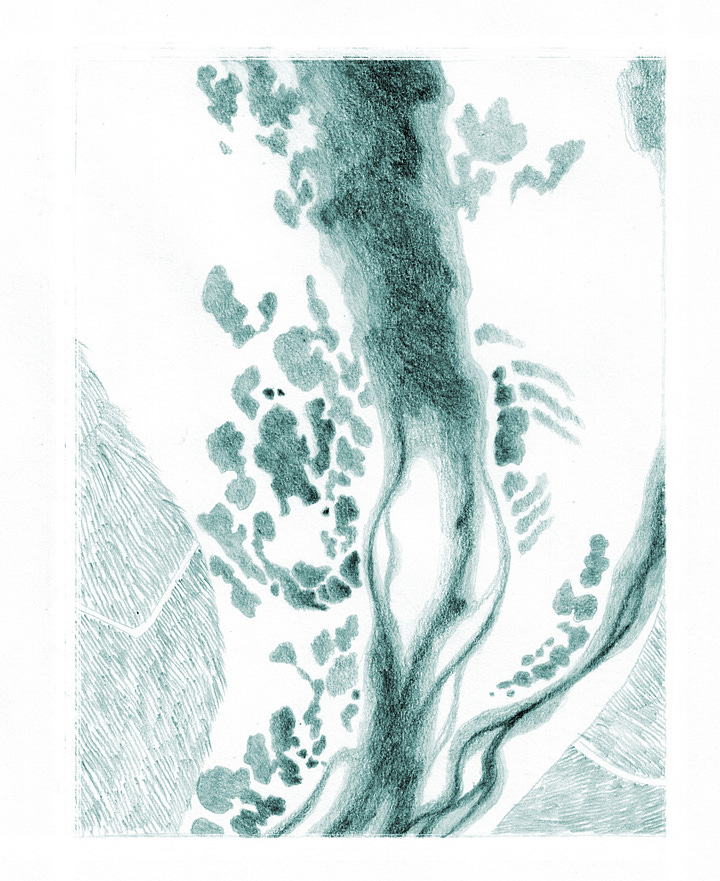

Kabini Amin, a designer and artist (fellow from the Moving Upstream: Betwa fellowship), is usually accompanied by her sketchbook-journal. The practice of noting and drawing her observations has been the interface between the self and the outside, often creating a barrier. She reflects that -

The scale of this endeavour and the required openness with unfamiliar people and places was pushing through my screen. By having to be vulnerable, Life, Landscape and the River tore through my skills as an artist, impressing themselves directly on my page. It feels obvious to say this in hindsight, but when I look through my drawings from the fellowship, they look like what the land and people felt like: fragmented, intimate, weathered, raw.

An architect, product designer, journalist, biologist, children’s book writer are among the many diverse individuals that have been part of the fellowship so far. Like Kabini, this experience of knowing the river has impressed itself onto the craft each of them practice, their work and their personhood - walking facilitated the ease of such a confluence.

And walking with partners, “indulging in those moments of pause to try and see what they(the other) did so easily, opened my mind to noticing what I ordinarily do not” shares Prerana Anjali Choudhary(also a fellow from the Moving Upstream: Betwa fellowship). This way for a community to find itself - one under which flow silent, strong currents of shared intent and bound by a visceral experience - is powerful in its ability to kindle meaningful exchange and discovery. It imbues a sense of collective ownership towards issues and offers a space to find interests that intersect and seeds the possibility for ideas to emerge from these intersections.

Germination of Ideas

Ideas journey much like a river. Gushing forth at times with a formidable force and determinedly trickling through during others. It has its sangams(confluences), its forks and points where it dramatically changes its course. Regardless of form, it is characteristically alive and responding to the environment, people and realities around. The trajectory of India Sand Watch was no different.

Over the course of Siddharth’s walks along rivers in India, a recurring scene was that of mounds of sand, earthmovers, cranes, trucks being loaded and the criss-crossing trail of tyre marks. Stories, observations and repeating evidences of sand mining began to collect and register, revealing the scale and extent at which it was operating.

Illegal sand mining is a challenge that has a huge impact on riparian communities and ecologies - disrupting the natural habitat of species, changing the course of the river and altering the relationships people share with it. Despite legal safeguards and revisions in policy, there is a collapse in implementation and monitoring that has led to a “paucity of public information regarding where sand mining takes place, the volumes of sand extracted and who is licensed to do it.”

An idea is sparked at times by the most unassuming of events, and it grows in curious, non-linear ways. In March 2018, a tweet by the Punjab Chief Minister prompted Siddharth to take note and respond, becoming the nudge that led to a snowballing of experiences, observations and the will to act.

Using Google Satellite imaging he proceeded to mark out all sites of sand mining along the Sutlej. Akshay Roongta, a close friend who was then consulting independently and is now the co-founder of Ooloi Labs, responded to the thread by suggesting the gamification of this method of identification. He cited the example of Sarah Parcak and the ‘space archaeology’ software - GlobalXplorer - she developed to engage people in finding and preserving archaeological sites through satellite images. Much like traces of archaeological looting on the ground, marks of sand mining activity are pronounced and form characteristic patterns - they are commonly described as resembling a fishbone, cauliflower or fractal and are easily distinguishable. This was the fundamental premise on which the idea was based.

Informed by Siddharth’s trysts and observations, compounded by the twitter thread and shaped by Akshay’s inventive spin to it, an environmental accountability mechanism for sand mining was incepted. In its initial conception, a core part of it was that identification of sand mining activity would create change. The imagination being that this was all that the community would need for change making - an understanding that would evolve over time.

Akshay and Siddharth were keen to build Machine Learning into some of the functions of the platform. The high cost attached to it threw a spanner in the wheel, forcing them to pause and other commitments and projects eventually took precedence. For a period of time, the platform seemed to have lost steam. However, under the veneer of a lull, it was in fact gestating. And in the world outside, technology and its accessibility continued to advance - remote sensing data became far more easily available and from approaching tech service providers, they could now imagine building and training ML models themselves. Siddharth so happened to be the convenor of the India Rivers Week in 2020, the theme of which was Sand mining, thus deepening his understanding of the issue.

In the mean time Akshay along with Abrar, Sheneille, Prachi and Yashna co-founded Ooloi Labs and they started work on the Open Knowledge Framework which was being designed ground up as a configurable system to take in varied kinds of data both quantitative and qualitative, with a team that worked closely with partners to help integrate their custom platforms into campaigns and programs. This was the perfect sort of vehicle to take the idea forward.

In March 2021, an article by South China Post on the work and its possibilities generated renewed interest and they began pitching it, albeit in a different way -

The second time work restarted on this idea, the approach was to make advanced technologies one component of the work. More important was the need to build an ecosystem where the data was actionable. The focus was on network building, capacity building, engagement with civil society, official actors, non official actors. Creating pathways for action became a priority. This is where the restructuring happened to what would become India Sand Watch.

- Siddharth

India Sand Watch was officially launched in August 2023. It enables the creation of and hosts clean, usable data sets to track sand mining activity. Built as an open tool, the portal acts as a public facing archive that includes data in the form of news articles, survey reports, guidelines, tender documents and legal proceedings. This bundling of data sets unlocks the agency of multiple actors like journalists, environmentalists, policy makers, lawyers and researchers by facilitating the ease of cross-referencing evidence.

The incorporation of technology through remote sensing, geolocation tools and the platform itself follows in the tradition of citizen science engagement, inviting those curious and concerned to participate and contribute in meaningful ways thereby asserting their stake in the world around. Leveraging satellite imagery is particularly relevant to ensure the anonymity and safety of those choosing to engage with the issue. A feature crucial when contending with an industry that functions with impunity and where voices are frequently threatened into silence.

Over the last few years of Agami’s work within ecosystems to effectuate social change, we have observed over and over again that access to justice challenges in the country cannot be solved by one product or service, however transformative. The issues we contend with are not monolithic and there is a need to enable changemakers at every level, however big or small, to make a dent in the problem. The novelty of Veditum’s effort is in this creation of a range of offerings, cumulatively opening multiple entry points to engage with, discover ways to relate to and participate in addressing the state of rivers.

Sense differently, solve differently

Returning to walking, her journey along the Betwa made Prerana think of the collision of worlds and realities that occurs when traversing through unfamiliar terrain. She wondered if -

We as students, scholars, professionals and policy-makers fail to ‘see’ because the structures we have built around us offer no possibilities? To pause, reflect, listen, understand, and empathize? Is that where the gap lies? Between the privileged and the dispossessed, between the urban and the rural, this cerebral, but also physical and fundamental difference of how we relate with time and space.

In asking some of these questions, being limited and in a state of stuckness is acknowledged and this awareness is the precursor to the beginning of movement. This movement is vital to breathe new life into the environmental justice problem. For a dent to be made, there needs to be a perennial flow of possibilities and access to them. Experiences and opportunities must travel through different worlds, cross-ventilating and cross pollinating thought - birthing new approaches and increasing our propensity to adapt to a rapidly changing reality.

India needs many more river-walkers.

Artwork by Kabini Amin